An introvert's guide to creating things people want

Understanding people and how they want is challenging. We have more information than insight and less time than ideas. Let's tackle those!

Ended

When I was the Chief Happiness Officer at Strikingly, I made many mistakes -- one instance was this: I A/B tested my new onboarding idea, with the goal of being right, and with a lot of self-confidence riding on the results.

I felt too embarrassed to acknowledge that mistake for several months!

Looking back, I realise it was a pretty natural, though serious, mistake to make. It's helped me learn things about my mindset, processes, and commitment to rigour.

Here's what happened and what I'm practicing now...

It started with the joy of a new idea -- I was proud of my creativity and customer intuition, for coming up with this new onboarding process.

I set out to test it. I expected it to work, of course.

I was passionate about the idea, and spent time making a really great "B" version to test against our normal "A" version. I built more than what was required for an initial test.

First week of results: great! Statistically significant. I shared my joy with my teammates.

Second week: not so good. Insignificant.

I was disappointed -- I felt that my previous excitement was unsupported and possibly incorrect. Now, my ego was more invested in the results coming out in my favour, as it seemed like they were before.

I made the "B" versions "better," different from one another... making the A/B test essentially useless, because data wouldn't be able to explain the results.

We kept both versions up for a long, long time, because I really liked the concept, and it wasn't significantly worse (or better). The idea lost momentum, and I felt deflated.

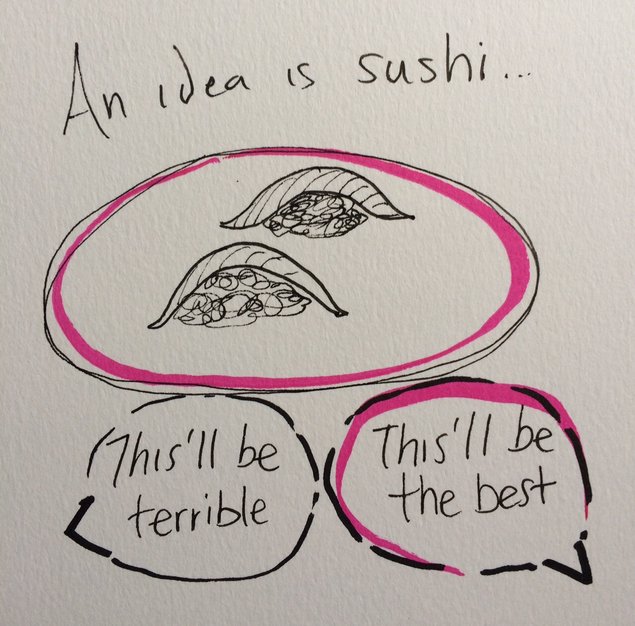

Any metaphor could work, but let's do a food metaphor: an idea is sushi.

I can go in wanting to notice the mix of freshness, creaminess, and wasabi, or I can expect it to be drab. It's likely I'll feel what I'm expecting to feel. This way of eating sushi would be poor science, because my expectations directly influence the result.

In contrast, an A/B test aims to be scientific -- it aims to show that an alternative idea is better, not by trying to prove it right... but by trying to prove it wrong.

If an idea is on track with the truth, it will confidently pass even tough tests.

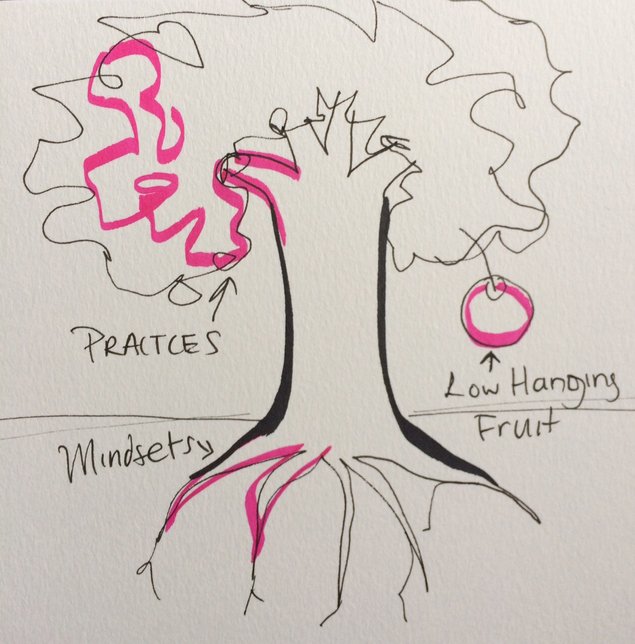

The A/B test is execution, and in some contexts, a low-hanging fruit.

But, testing grows out of a mindset of seeing everything in the world as an experiment, of acknowledging that we don't know, and expressing a desire to know.

The experiment mindset says that we can become aware of our biases and assumptions, and accept that conditions and facts will change.

The experiment mindset is easy in theory, much harder in practice.

How does one practice a mindset?

Here's a few things I'm practicing:

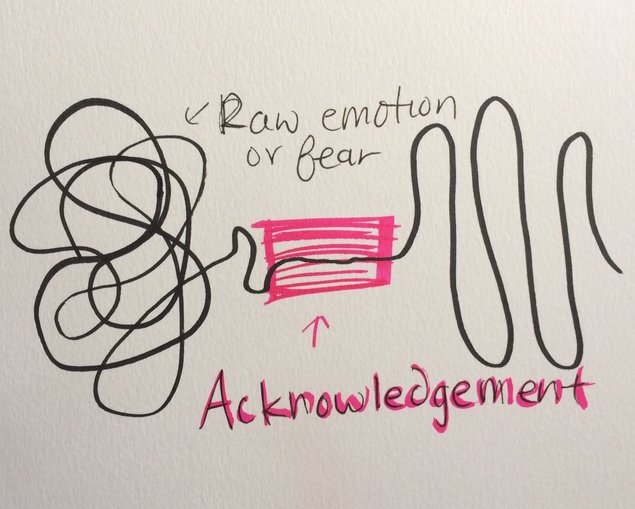

1. Acknowledge my excited intuition. Acknowledge emotional, egotistical attachment to the result of something, and aim to let it go.

I often say things like "I feel excited, and I can see my passion getting in the way of a fair assessment," or "I imagine that getting insignificant results on my test will mean that I have poor intuition and understanding... I acknowledge and let go of that fear."

It seems strange, but just acknowledging a feeling or fear helps it to calm down.

2. Justify all sides of the argument or test.

I naturally support my idea more, so I need to take time to list out reasons for why our current execution, or alternatives, are better.

To quote Charles Darwin:

“I had, also, during many years, followed a golden rule, namely, that whenever a published fact, a new observation or thought came across me, which was opposed to my general results, to make a memorandum of it without fail and at once; for I had found by experience that such facts and thoughts were far more apt to escape from memory than favorable ones.”

3. Practice seeing the uncertainty in everyday things.

I do many things each day where I feel quite certain of the result -- sending a email, asking a question, sharing an idea. But, because I feel certain, when I get an unexpected result, I am frustrated, saddened, or angered.

I now try to say to myself, "I expect X, yes... but what if Y or Z?" If I feel these seemingly certain things are a little less certain, I can be more curious about the result.

And then, I can be even more curious and open-minded about truely uncertain things... like A/B tests.

Happy Wednesday,

Angela O

angelaognev@gmail.com