"New Dawn" is an experimental novella based on the Nepali civil war. It is about a small group of Maoist leaders and fighters connected in various ways to the insurgency.

Subscribe now to get early access to exclusive bonuses for my upcoming book, New Dawn, when it launches.

Subscribe to updates"New Dawn" is an experimental novella that is partly based on the Nepali civil war involving Maoist rebels and government forces that took place between 1996 and 2006. It revolves around the experiences of a few senior-level Maoist comrades who recruit, train and lead other lower-level fighters from the beginning to the end of the insurgency. The book attempts not to place blame for the insurgency on any political sides or individuals, and instead attempts to show how the very understanding of the insurgency is complex and difficult. It is, in a sense, a "fictional gap analysis" of the gaps of information and knowledge from the standard narrative of the civil war that has been provided through the media, and especially addresses an international audience who did not live through the war first-hand. It has been described by some as an attempt at detailing the Nepali civil war as if it occurred in an "alternate reality." The book attempts to place the civil war in the midst of other concerns in the lives of the people involved in it, such as their quests for a better life, their pursuits of jobs and dreams, and their love affairs as they occurred within and outside the jungle insurgency. Ultimately, the book considers how the ending of the civil war did not solve any political and social issues in Nepal, and perhaps led to more problematic realities in Nepal than before the war began, with more potential for discontent, violence and division along ethnic and class lines.

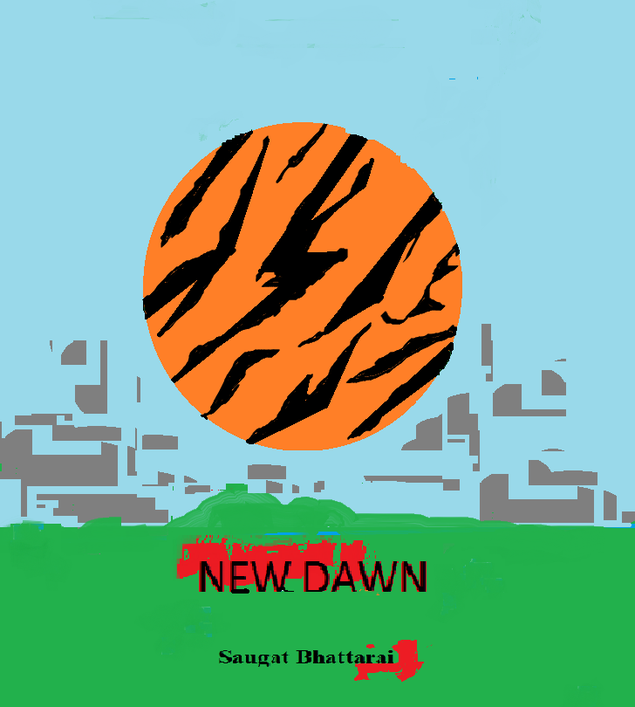

Experimentation with structure is one of the main features of this book. The six chapters all contain separate plot points, but the more relevant knitting or uniting elements of the plot are certain images and ideas that repeat throughout the book. For example, one of the main knitting elements is the image of the "Cosmic Tiger," which is a "cosmological animal" that features in the superstitious fears and anxieties of some of the tribal Maoist fighters. This image of the "Cosmic Tiger" repeats often in all the chapters, but in different contexts and for different reasons. Another very important structural feature of the book is its lengthy sentences.

Chapter One of the book is called "Raniban Ambush." It introduces the three major characters "Comrade Sunray," "Comrade Dawn," and "Comrade Codebreaker Alpha." It focuses on how the civil war began, and the plot points are mostly fictional, apart from the dates. Comrade Sunray and Comrade Dawn's love for one another is also imagined, and Comrade Codebreaker Alpha's importance to the civil war--given his ability to do complex math--established.

Chapter Two is called "The Fall of Dawn," and this chapter begins to identify some of the problematic issues with the civil war. Comrade Dawn eventually leaves the jungles because of her dissatisfaction with how the war is being perceived by the other two head comrades, as well as because of the occurrence of the "Mugling incident," where fighters come to a small hilly town called "Mugling" and, in mistakenly celebrating Mugling as a utopia, almost reveal themselves as Maoists to the police.

Chapter Three, entitled "Satellite Paranoia" further questions how the Maoists might have perceived the United Nations which was also active in Nepali politics at that time. Comrade Codebreaker Alpha's paranoid beliefs that the UN has a weaponized satellite called the "UNSAT" drives the primary plot. A rift between Comrade Codebreaker Alpha and the couple Comrade Sunray and Comrade Dawn is also established.

Chapter Four is called "Comrade Moonbeam." A new head comrade, whose gender and facial features remain obscure to the Maoists, is introduced. He/she is responsible for administering morphine to the injured soldiers, and largely addresses one of the interesting "gaps" that guides the whole book: what painkillers were used on the injured fighters, and what can be revealed about the parties from which these painkillers were acquired? In the absence of answers, Comrade Moonbeam and morphine drives the plot. At the end of the chapter the Maoists experience an event akin to a Greek tragic drama, and Comrade Moonbeam, like Comrade Dawn, ends up in a mental ward.

Chapter Five is called "Mark, A Reporter-Without-Borders" and follows Mark's journey from the fields of Scotland to pre- and post-civil war Nepal, where he works as a reporter-without-borders. Like Comrades Dawn, Codebreaker Alpha and Moonbeam, Mark also eventually loses his mind, partly by the burden of covering the whole insurgency. Mark's relationship with his ageing mother, who wants a brick from the fallen Berlin Wall, is also developed, but it does not stop Mark's sad fate in the mental ward. The end of the civil war is addressed, and the lack of grand monuments for it in Nepali space questioned and criticized.

Chapter Six is called "New Dawn" and in it Comrade Dawn recovers after the civil war is over. Comrade Sunray's own problematic searches for an object of desire are elaborated in the post-civil war context. At the end of the book, a great wildfire rages on in the hills of Nepal, and it could be assumed that Comrade Sunray might have died because of it.

The audience for 'New Dawn' would be people with excellent English reading skills interested in engaging with the problems in Nepali politics and political history. People conducting informal, college or university level research in Nepal, especially regarding its society, culture and politics, as well as those interested in the progress that Nepali writers have made when writing in English language, would find the book interesting and relevant to their intellectual pursuits. Furthermore, all readers interested in experimental content and structure would enjoy 'New Dawn' because of its innovation and frequent disregard for rules and norms about structuring the plot and developing the characters. Readers interested in challenging and dense work, in abstractions rather than ready-made answers, would enjoy this book greatly. That being said, this book also raises important thought-provoking questions about how the civil war that took place must be accounted for, seen and explained, opening up the space for readers to research the civil war--and indeed other civil wars--on their own, asking their own questions. Readers who have read the experimental and dense works of Thomas Pynchon, Don DeLillo, David Foster Wallace and William Gaddis would also find 'New Dawn' enjoyable. Readers who are interested in long sentences, elaborate imagery, and thinking about books extensively after they are finished with reading them would enjoy this book. This book would also befit a high-school class setting or a book club because of the potential for it to raise discussion, and even arguments, rather than providing clear-cut answers to easy questions. There is thus a potential for this book to be sold in Nepal, India, China and the English-speaking countries of the West.

I plan to support the themes and thoughts that led to this book by dedicating a blog to it. For example, I want to write short political essays on why the Nepali civil war has not been followed-up by the building of significant artistic monuments to its martyrs. I would try to get such essays published not only in a blog, but also in Kathmandu's major newspapers. I would also highlight the importance of the subject-matter of this book, and how it shapes Nepali politics, culture, society and psychology today. Additionally, I would not only focus on writing from a largely social science perspective, but also write short essays on the metaphors employed in the book. For instance, I would ask and explore answers to the question "What if the Cosmic Tiger, a character in the book, was in fact an alternate name for the sun, as the book's cover suggests?" By answering this question, and other questions like this, I would suggest how I too am in the process of reading the book that I wrote, that the meanings that are found in the book are not concrete, certain and "set in stone," but always open to interpretation, and depending on large part on the patience and dedication of the readers reading it even if much time has elapsed after they first read it. I am open to creating and building an online forum where the book can be discussed for its meanings and metaphors, that is, where the book is considered strictly for its artistic merit rather than only as a social and political commentary.

Title: Gravity's Rainbow

Author: Thomas Pynchon

Publisher: Penguin Classics

Publication date: 1973

Description: A postmodern novel about the second world war.

My book is different in that it is clearer and suited to a broader audience. It is also much more experimental structurally. It uses sentences and plot points that are more aesthetically pleasing than Pynchon's; it can be considered more poetic. It is also more relevant to global audiences today because of its subject matter.

Title: Carpenter's Gothic

Author: William Gaddis

Publisher: Viking

Publication Date: 1985

Description: An experimental work with long sentences and recurrent imagery about a set of dysfunctional characters based in suburban America.

My book is different in dealing with important sociopolitical subject matter in a far more head-on, direct way than Gaddis' novel does. Even though his work deals with issues of racism, its focus on the African continent makes it a rather tried-and-tested treatment of the issue. My book deals with ethnic-based miscommunication and class-based poverty within Nepal and would interest those readers who wish to look and think on such issues that is particular to local situations and to a certain specific time and place. Moreover, the experimentation in my book makes it more entertaining than Gaddis', although both books employ structuring that is not based on chapters alone but on recurrent images. Gaddis' extensive use of dialogue also gets tedious at times, and does not allow for the plot to develop as much as readers of a book would prefer, with the end-result being something akin to an experience at a theatrical drama or a film than something unique to a novel. My book is much more concerned with engaging plot than the extensive use of dialogue.

Saugat Bhattarai studied Philosophy with a concentration in Social Policy in George Washington University in Washington, DC. He has taken classes on policy and politics, international development, personal identity, ethics and history.

He is also interested in making music, paintings and has written lots of philosophical notes on technology, politics, Buddhism and reality in general in his notebook. He is waiting to develop some of those thoughts into essays, news articles and books.

Chapter One: Raniban Ambush

“Power,”

Comrade Sunray had said that day, pointing at the beads of light in

the city below, “is now sensitive, now ready to strike without

proper judgment, ready to crumble down in self-pity the more it

misses its target.” They were in a patch of jungle which they could

not name, for it had been recently formed as the expanse of Raniban

had been cut through by a major supply route for the police, and so

this one part was a jungle all its own which nobody had bothered to

name. At a small police post just recently abandoned out of fear of

the Maoists coming, a police-radio had been found in the trashcan,

carelessly thrown there, and with a bit of a tinkering Comrade Sunray

and the other Maoists could hear the messages between the various

police patrols underway on this night. The policemen in their patrols

did not know that Raniban, their Raniban, at the heart of

Kathmandu, had been infiltrated, just as they had passed by with

torchlight shining into the thicket, the dark, which they dared not

tread, for the fear that had come when they found the Maoist

pamphlets to be convincing to them, its exclamations making a

commanding noise in their hearts. And with the jungle all more or

less Maoist-controlled now in the police's flawed worldviews, they

thought something would come from within it, like a large, gooey,

alien pair of hands, to take them in, into the fold of the world of

leaves and snakes and trees, and find themselves in the midst of a

tribal dance of “Tharu Maoists” around a raging fire, the

policemen all tied up and groggy, and the Tharu Maoists hooting and

howling around the fire, giving no indication of when desperately

needed food and water would arrive, or if rations indeed were as low

as the papers complained and they were

the food, or at least had to die, tied up and, just like that,

without a morsel to eat, simply a ceremonial object in a fire-side

dance. And even if one policeman were to escape from that horror, as

some policemen did, when they staggered naked and mad to some village

which had no idea that the insurgency was going on in the jungle

right next door, he would still most likely die, for the poisonous

substance he would have had to eat at their ritual and for the

ancient trapdoor he would step into in the delirium from ingesting

that poison, the trapdoor that opened to man-killing spikes. So once

he was in their jungle world, that was it, the end. And the only hope

he was sold on, well sold on, what made him quiver and shake with

fear less than he thought he would when staring into that dark hole,

on that dark night, was that the United Nations, with the more

powerful armies and fully in the know of the value of human life,

even a Nepali's life, gave the hope, the rather false hope, in

sincere meetings in the halls of power, and with various public

service announcements with the maudlin actors, that it was

excessively concerned, excessively, and so its forces would literally

jump into the jungles of Nepal to save the policemen from the

Maoists, literally leap wildly into the jungle with a soldier's

bravery, never fearing for their own lives on the line. But this was

excessive hope over a convincing advertisement's images, that was

all. At one point Comrade Sunray had worked for an NGO and had

learned a thousand ways to be harshly critical of the UN, and he and

Comrade Codebreaker Alpha had extensive debates about what exactly

was wrong with the UN, whenever they, in camouflage, sat in the

thicket by a remote dusty road and a huge white UN vehicle passed by,

as if the two of them were watching cars passing slowly by from a

cafe in Paris, so relaxed in these debates they would be. But the

first sign something was off was enough to transform them into the

most serious jungle fighters the world had seen.

Comrade

Codebreaker Alpha hushed the conversations among the other fighters,

concentrated on the police-radio's talk, to figure out exactly the

where and the when, using the coordinate geometry-- the slope, the

distance formula, the mid-points--he had always equated with his rage

when he had found himself doing the coordinate geometry textbook's

more advanced problems well into the night, wondering why he did

them, as beads of sweat broke on his brow and an important life

called. At first he had been unable to recognize it despite its

clues, this Maoist life. There had been intense concentration on his

face when he read the math problems in which some hypothetical

individual had tried to profit at someone else's expense, or when the

laborer had to carry sixty kilograms of a load on his back, say, and

sometimes he as the problem-solver had had to add more load upon that

to solve his little math problem, as if the laborer he was thinking

of only existed on the pages of a math textbook or copy, the real

laborers being denied the attention they needed by these hypothetical

textual ones. But he did the math problem, arrived at the unjust but

mathematically correct solution with gritted teeth, with rage now

formidable and well developed, the page filling with mad numbers

while he, in his heart, had already gone to the nondescript outskirts

beyond what mattered in math, beyond the squares around the

coordinate geometry graph where tried-and-tested solutions would have

been, beyond state power, to unnamed jungles far away, going so far

away due to a dedication to the laborer—the one who was heavily

burdened, the one who existed in mathbooks more or less without

families, fully laborer, that “atomized individual,” as

intellectuals called him dismissively in the parlance. And whenever

he looked into the eyes of the Maoist fighters on patrol, he wanted

to let them know that he saw beyond the numbers even as all they saw

was him tinkering with the radio and writing numbers down. He wanted

to share how he—and his friends-- had burned “Optional-Math”

textbooks after the SLC exams, and had felt a burden he had never

before known or named lift, a burden of oppression, of

knowledge that had always oppressed him. It was for the first time

then, as the fire threatened to burn his fingers, that he had decided

on taking a radical political path. But he had never told this story

to the fighters because they did not know the SLC, and so he kept

quiet instead, and also kept quiet like that about a lot of other

things, very very patiently waiting for the day when they would know

what the SLC was. And he would teach them then, as they understood

it, wide-eyed, just as they began ever so slightly to desire to take

that exam, to see what it would be like, at that precise moment he

would teach them how to problematize the exam and kill the desire

to take it. At this moment however, only Comrade Sunray and

Sunray's comrade lover Dawn knew his story. Intrigued by his capacity

to do complex math, they had asked him about his life, and both had

nodded their heads in admiration vigorously, and looked to him and

his math projects—the formulas that he invented—and thought how

the knowledge of this young man, this unassuming codebreaker, had

literally made their insurgency into the thousand-strong cause that

it was today. And they had dreaded the future, visionaries that they

were, the future distant but not inaccessible to them, but

which Comrade Codebreaker Alpha himself had not yet seen,

that future when the

insurgency would be done, and they would all come upon the proverbial

fork in the road, and one would go his way and the other would go his

own way, once united by the insurgency to be divided when new paths

opened in their respective lives. And they wondered if, on top of all

the mathematical divisions he had done in his head so far, would he

do that division in his life,

that last division, the one that mattered the most?

Comrades

Dawn and Sunray had met at a UN-organized seminar of NGOs and quickly

fallen in love because they had both been going through a difficult

time and each had needed an outsider's view on how to solve life's

issues. They had been in a resort and had looked from the wide-open

terrace one morning at the jungle in view, and in the beginning they

had hesitatingly articulated their problems as if they were personal,

but found slowly that their problems were political as well. And then

Sunray, ever the good speaker, had summed up their problems, when the

sun had set below the huge hills in a magnificent scene: “We are,”

he had said, “at this moment, in the decline of Nepal: poverty has

never been worse, police power never so corrupt, women as oppressed

as they were a hundred years ago...the decline of Nepal is all around

us now, and I see no place for hope, for survival.” And then two

years later, on a pleasant rainy night in Teaching Hospital in

Kathmandu, Sunray and Dawn's child, a daughter, was born. A beautiful

daughter she was, but blind and deafmute, with no chance of surviving

without the care of her mother, never hearing nor seeing even the

pleasant rainy night when she had been born, the night which leaned

towards her, demonstrating an intensity of anxiety about her

well-being which would only lessen as night after night elapsed. A

year into her life she died, leaving a scar in Dawn, a rage in

Sunray, and in the steps of their departure to the jungle there was a

hurried fleeing from society too, a fearful fleeing from the

ruthlessness of life as they saw it—the life, the air, the

hospital, the home, and then the UN, the state, the police, the

political establishment, capable all of these of taking away

daughters from parents, as they saw it. It was in Rolpa, much later

in 1999, when a police barracks

had been taken over by them, the Maoists, and it rained so much so

that it rained the roads away, with the police thus stuck many many

hills away at night, so that the barracks, for the time being, were

theirs, it was then that the fighters had slept in the barracks to

avoid the rain, and had, in bunk beds, shared their stories and

secret pictures, and Comrades Dawn and Sunray, looking out at the

rain, had from a deep purse which no one had known about shared a

small picture of their late daughter, and had wept openly in front of

the others for their loss. It was on that night that the two of them

felt the first signs of intimacy and love from the fighters, who had

come around and consoled them, handed them blankets and tea and such,

and they, in gratitude, had written a kind of “Constitution” or

“Code of Conduct for Guerrilla Warfare,” where they had listed as

the first item the rule “Aim for the heart, never shoot at the eyes

or the head, for he or she must have in the next life the ability to

know and learn.” And it followed on from that, it flowed and

flowed, this “Constitution,” till the sun rose again and still

nobody had slept in that barrack-world: the victory over the police

of the previous night was significant, sure, but even more so was the

intimacy between the Maoists, the togetherness, the community that

they felt, and the rain, and Rolpa cut off from the bad

world...everything had played its big part. Before they left for the

jungle again they stuck a Chairman Mao poster on the barrack's wall,

so that, if any one policeman almost convinced to come over to their

side wanted to, he could put a “human face” to all this

overwhelming war and bloodshed, and hence connect with the

insurgency, if at first through nothing more than the desire to know

this man whose face was on the wall, this one they called Chairman

Mao, whose face had become on the order of a very important sign, a

larger than life sign, only to the poor and the fighters, of

course, and not to the privileged folks who also sometimes stumbled

into the barracks camera in hand, who had seen it many times in dorm

rooms and saw him as no different from any other celebrity.

A

glinting blue police-van grew visible just after Comrade Codebreaker

Alpha had told the rest to be ready. A slow-moving police-van, quite

obviously not in-the-know about the Maoist infiltration, shining a

powerful torch—a gift from the US police-force—into the thicket.

Wolves recoiled when the powerful light hit their eyes—growled and

seemed to want to restart the first wars with men such as these--oh

how long ago--wars which had driven the wolves out for good--or so

the men thought—till they came back to Raniban under cover of

night, having devised a strategy to win while running along a path to

the jungle no one else knew. The police torch also shone on the

drug-users, the tapes,

who wilted when the light hit them, collapsed unto themselves,

groaned, moaned, “go away...go away...” wanting their drug highs

to be resumed, pale hand over their eyes, cursing the police, making

it obvious that they had some fragments of the revolution in the

shallow drawers of their bedroom cupboards, next to the old broken

cigarettes and cool blue lighters. Comrade Dawn, nimblest and

quietest of the Maoists, took her place at the back of the fighters,

and was ready to do what she had done in all the ambushes so far: use

the megaphone to guide them, encourage them, all

of them, including her husband Comrade Sunray. Or sometimes make

chant-like sounds to disorient the enemy. She was very good at that,

at playing “the witch” the young policemen had stoned to death in

their villages as ruthless teens trying to demonstrate their budding

bravery, as if she were that same witch coming back to haunt them

again. She climbed an old tree and had a proper view, and saw Comrade

Codebreaker Alpha was ready to throw a flare into the path to ready

everyone for the ambush. Then the fighters looked at one another.

They were always allowed this ritual, no matter how critical

the situation, this chance to say wordless their last goodbyes, not

to their families in their hearts, nor their village friends

drifting before their mind's eye, nor to memories of playing on that

tall village swing at Dashain

time during a childhood now long gone, when dear Father had been

alive, but to say goodbye to the other fighters, the other comrades,

the soldiers next to them now and here, in the muck and mess

with them, to affirm this

life, in this moment, now with a past they had all

absolutely left behind, gone the long walks through jungles singing

songs of the coming utopia, and learning to get accustomed—among

shy giggles—to the heavy guns that they had been given out in that

small ceremony they remembered as if it had been yesterday, in that

fantastically beautiful clearing somehow just there, just meant for

them, as if the jungles, too, were—naturally--on their side, till

it was time tonight to say goodbye. They then moved a little down the

hill and trooped towards the patrol route, under the cover of

darkness—or so they thought. For they did not know—they who only

knew the maobadi batti—that today there had arrived to the

police force, in the cover of the night, just a few hours ago, a

hundred or so night-vision goggles, one of which was being used by a

sharp young policeman in that police-van. So that if the police-van

reached a proper set of coordinates, and the fighters did too, the

policeman with the night-vision goggles would see perfectly the

Maoist insurgency coming to ambush them.

Dawn

and Sunray, right before starting the Maoist movement, had been in a

white NGO jeep stuck in a part of Krishna

Bhir because of a landslide in the works, witnessing the sheer

power of angry nature as it tortured the human world stuck below, the

huge boulders up there which could roll down at any time, the stuffed

and overstuffed jeeps and cars and buses which could quite easily be

crushed like bugs. The plan, when

they knew no more than to pronounce the word “freedom” clearly in

Nepali, when it wasn't even clear to them what they exactly

meant by that word, except that they felt its insistence on their

politically conscious lips, had begun a year or so ago, when Sunray

had begun his reckoning of the moment in which they lived and had

worked through labyrinthine analyses of obscure newspapers. And one

night he had begun to think of uniforms, and then of the soldiers to

wear them, and then onto other historical manifestations—in Latin

America and elsewhere—of armed struggles by the poor and oppressed.

He dived into books of jungles so thick and dense that he quickly got

lost in them, but it was so exciting that he lost his breath, and

went therein in the silent night deeper and deeper, in the thickest

of a jungle which had not yet known a machine, where he saw the ghost

of Che, or dreamed it, and it was always beyond the stifling leaves,

always camouflaged Che's clothes, with perfect visibility not really

possible, not in a convincing way. By the blue moonlight streaming

in, he wrote to himself something which touched his soul: “To be

such that one, while in reality, is a figure in a dream, not properly

seen for the light is always rather dim, and not properly known, at

least not by the onlooker within the dimness.” And it was not an

aimless foray into the jungle after a while, but he began to connect

with it—he felt like he had a map of it somewhere in his

head—because it led, when he finally knew where and when to stop,

to dawn, to that young bright light piercing through the canopy, to

colorful birds so cheerful at that and to a fawn stretching to reach

the first dewy leaf to be had for the day, and he felt a thrill like

that which little children enjoying nature for the very first time

feel, before he woke up and was alert to a world robbed of such

incredible jungles and pathless ways of life as he had seen, and

robbed of the potential, which was evident while driving in the NGO

jeep through jungle after jungle, to be less visible, to fight for

that right, that right to be less visible, to drop out,

to not live under oppression and an oppressive light, but to live a

life under that light which is more playful, as Dawn was in the

jungle, and this came to his mind like a painting, a painting with

Dawn in it, but only as if she was a part of the jungle, as he took

her in his mind from that NGO jeep they were in and placed her in the

jungle out there, and followed her in there. Their great secret was

that theirs was a life of the jungle, that the jungle for

them, their daughter lost, was not a means to an end but an end in

itself. It was where they would live forever, they thought, to guide

others who came to it, the poor and the oppressed, the needy

wandering in in desperation—that indeed was the end of it, to live

close by the hidden path, to be that man and woman who guided those

who sought that hidden path. And then Sunray said to Dawn at Krishna

Bhir, pointing to a massive boulder about to tumble down, “Either

we move on as the movement to the jungle, or we wait and we get

crushed here and now.” For Sunray, this life of rebellion was all

he would do henceforth: his new life on the whole had begun, and he

was its leader.

Dawn

had felt overwhelmed when Sunray had asked her to go with him into

the jungle. And as the anger at the world grew inside her too, she

felt more creative, as if a part of her was also asking in her heart

what exactly it was she would do in the jungle. So she felt more

creative, and that creativity seemed to hint to her her path, her

purpose, and so she accepted it and began to paint. She painted the

uniform they would wear, the colors' exact shade she chose, and she

put muse-soldiers in wide, fantastically colorful paintings of

utopia, painted out as rainbows in the blue horizon and bright yellow

shapes which looked shapeless, friendly and warm, the place of full

equality, of no oppression, the place of freedom. She was passionate,

her thoughts infused with a feeling

of utopia, a feeling which, despite her years in

boarding school in Kathmandu and her troubles with her family, was

still with her. She had a feeling of utopia, which had somehow

crept through and bloomed, a fact which, if you told any other NGO

worker, would be laughed away because he would never believe that in

the life and world of Nepal a utopia could be imagined, because he

would consult only the reports and graphs which gave a bleak

portrait, but she had really felt

it—it seeped through her and dripped from her into every single

painting she made, in every one it was there. Then when she

saw on a college dormitory wall a poster of Chairman Mao, she began

to add more people into her paintings, people working in the fields,

with the machines that the people had mastered and which were on the

whole created by the people themselves, and such paintings she made

could, if they had to be labeled, be called “socialist-realist.”

And when it all began and gathered in a whirlwind, in a force, a

rage, when they entered the jungle wearing the uniforms they

themselves had stitched, and guns half-handmade and

half-manufactured, she took with her only her painting supplies, and

when Comrade Codebreaker Alpha made maps of utopia for the fighters'

benefit, she gave them her paint supplies to paint out their feelings

as they heard and saw what Comrade Codebreaker Alpha had to say, to

paint what the utopia that was mapped felt like to them. They liked

to use bright colors, and they had sheer will to paint more and more

and more, due to which they even made paint from the juices of the

flowers they found, and whenever a new rare flower they uncovered

within a fold of leaves they made paint from it and worked on each

new painting for months at a time. And those were, in sum, the days

before the fighting began, the “formative” days were those, and

on the whole, great days were those. She had stood before those

paintings, and, during painting sessions all of the Maoist-painters,

too, would stand and stare at their work with her, see the utopias

that had been within them, the dreams that had been there, these

expressions, these reminders of freedom. And it was all good to hope

that power did not reach into them, into everywhere and everything,

and that one day, one fine day in the depths of a quiet jungle, as

they patrolled like any other day, a faint cheer would be heard, from

far far away, that said that someplace in Nepal, or in all of it, the

utopia which they had sought and fought for had finally arrived...

And

the one policeman was not convinced by the whole thing, the one who

thought of Tharu Maoists gone wild in the jungle, not convinced by

the armed struggle which arose, its philosophies and foundations, the

news articles that criticized it or the ones that hailed it, the

documentarians that went to Rolpa and “objectively” filmed it,

the police heads decapitated but still frozen with looks of fear, the

politicians in more fear, the ferocious modernly dressed young woman

from the village adamant about taking a stand about it all, the

international actors who commented in the tersest of terms about it,

but who, he secretly felt, did not fully understand it, the one he

called his wife, who wanted him to quit the police-force, and knew

not that they wouldn't be able to go back to the village where the

fighters had more or less taken over, the ones he called his kids,

who were fascinated by the maobadi batti he had had to bring

home on account of the extremely long power cuts, because they, the

ones he called his kids, needed to study, grow up, and pass the SLC

and do still more beyond what he had done in his life, and settle

quietly into the sides and factions and regiments of the ones whom he

doubted, with his Nepali post-SLC doubt that had developed beyond,

but only just beyond, the iron gate to the graveyard. And he, that

one doubting policeman, was

the one shot dead by the rebel ambush at Raniban that night. It was

he who was killed right on the spot the moment the night-vision

goggles had registered a thousand-strong army of Maoists rolling down

the hill in waves, after which

the police-van, knowing it would have been downright impossible to

fight that force, fled the scene. As the police-van sped away from

the ambush with one of theirs suddenly dead, the policeman wearing

the night-vision goggles looked in the rearview mirror like a

cop-hero, and his look was greeted by the ambush coming onto the

road, running after the speeding van. And in its rage to catch up he

heard a voice articulating the decades and centuries of oppression

that he himself knew well in his heart, an oppression right down to

the first seed of the withering family tree, the tree which, huge and

ripe from eager procreation, takes a thousand years to die but is

surely dying from the very beginning, rotting from within even as it

maintains a facade of order when it sways gently and calmly in the

village breeze, losing nothing and gaining nothing, shedding nothing

and taking nothing, the branches adance and bendy, fresh and young at

the tips, fooling the wise old village man

whom those tips swooped down to greet, who knew nothing about

the tree but saw in it a positive picture of life and vitality, of

the hope of life, the beauty

of life such that even a tree that had lived for a thousand years

still wanted to live, to grow, bear as and when possible,

until it bore that fatal seed for which it had been alive all along.

And that fatal seed, that one doubting policeman lying

in between the force field radiating lukewarm old-man wisdom and the

cold underground, was now dead

in that police-van, now spirit, soul, between the system of belief

known as life, and the system of belief known as death.

Chapter Two: The Fall of Dawn

On a

monsoon day in 1998, a day off from training and education, a group

of twenty to thirty Maoist fighters from Rolpa had, in civilian plain

clothes and with Comrade Sunray, Comrade Dawn and Comrade Codebreaker

Alpha with them, descended down from the hills around Mugling to have

some fried fish and just to walk around. When they got to Mugling,

they found motorbikes with stickers of Che, and young bus conductors

wearing t-shirts with Che, and posters of Che on the teashop walls

and wristbands of Che on the younger teens, and so it had appeared to

the fighters, quite convincingly, that they were in some kind of

utopia, given that there were so many faces of Che in that place, and

so they had proceeded to scream, to scream: “We are in

Utopia! Utopia!” and dance around in the rainy streets, and behind

them the dark green towering hills were just about to join in the

rain, with gaudy bright red flowers, and little smiling red-cheeked

Mugling children who had seen cars and buses and trucks pass by their

whole entire lives, and when younger ran after these lives of

mobility fascinated by them, motivated by the question they posed to

drunk missing fathers when restless legs asserted themselves in bed,

“What is beyond those tall dark green hills, truck-driving dad?”

But as they got older they had stopped chasing trucks with dads, for

the life beyond had stopped being appealing, because labor had

been recognized in driving these long long bendy roads, and labor—if

nothing else—the Mugling children fiercely disliked. So instead

they sat and stared, as they had done today when the fighters had

leaped and danced in the rain shouting, “Utopia! Utopia!” And if

they, the Mugling children, had so much as made a single peep about

that, so much as narrowed their eyes at that strange sight, the

police would have found out about the Maoist fighters in civilian

clothes and shot all of them down right there on the road, and it

would have been a significant victory for the police. But the Mugling

children just watched, as they always did they watched anything that

traveled this road, eyes glazed over and staring from under the

rickety tables of their mothers' tea shops which lined the road, they

just watched the road, and, through the silence and resignation of

the Mugling children, the Maoist fighters survived what would have

been a massacre. And Comrades

Sunray and Dawn and Codebreaker Alpha too survived, as they were just

coming down from the hills to hush the fighters quickly and

vigorously when they heard screaming and dancing. “The Mugling

Incident,” as this almost-fiasco was called, was debated day and

night after the Maoists went back up the hills and back on patrol,

and the main comrades tried to make it clear to the other fighters

that despite the pictures of Che Mugling was not utopia, and

then a whole new education was imagined for the fighters, one which

relied less on dangerous concepts like utopia and more on an

accounting-for of the events that had happened around them during

their training and usual forays into the world of normal people by

making use of words that they understood well. Comrade Dawn was held

most accountable for the Mugling incident, and a rift grew between

her and some of the others: her educational approach, her heavy focus

on artistic expression, made her problematic. And one day not very

much afterwards, when they had been patrolling a very thick part of

the jungle, Comrade Dawn, who was fond of walking while daydreaming

towards the back of the patrol line, broke away from the line without

the others knowing, and walked a separate way through the jungle, and

she felt she was gone for good, that fateful day of the aimless

drift, until she heard a rustling in the leaves, the unmistakable

sound of footsteps breaking twigs, and, with gun drawn, she had

waited for something to emerge, and when it did she found it to be a

small group of Maoist fighters, who, when she had broken off had

broken off with her, to show that they were on her side. Wide-eyed,

staring at her silently stood they for whom her visions of utopia had

mattered more than anything else. Then one of them whispered, “Come

back, Comrade Dawn...come back...we believe in utopia....we will keep

alive the dream of utopia...” And she suddenly remembered her own

late daughter, looking at these young fighters and trying to

calculate how old her own daughter would have been then, perhaps

barely a teenager like these fighters were, perhaps a bit older...

They stood silently before her with their excessively passionate and

naïve expectation of utopia, and she felt ready to do anything

for them to keep their belief alive, seeing clearly for the first

time just how young they were, without parents at that age when they

needed help with tempering their daydreaming, and just for their sake

she turned back to join Comrades Sunray and Codebreaker Alpha once

again.

In a

sense it was to appease the very vital Comrade Codebreaker Alpha, who

had been angered by the Mugling incident, that Comrade Sunray drew up

a rudimentary sketch of the Raniban ambush and handed it over to him,

giving him a year or so to bring that project into fruition. Comrade

Codebreaker Alpha busied himself with the project—he was totally

immersed in it—and drew “meta-maps” on the jungle's muddy

ground, meta-maps which he said were maps of other strategic maps.

And as he consumed himself, totally occupied in the world of

map-making, he began to note changes on the surfaces on which he was

drawing: the muddy ground of the jungle in the hills was now giving

way to a different kind of ground: a harder ground, cracked in

places, with holes for rodents and snakes, no visible footprints,

dust rising from all places, surfaces that had not held seeds for

many many generations, the fields of the unfortunate, with the poor

Tharus confined to these barren places, with eternal famines the

government did not care about, or maybe could not do anything

about—and such drawing surfaces began to now contain slender

footprints of anxious folks that he did not want to disturb, which

led to the Tharus themselves in their hot huts. And as Comrade Sunray

was speaking to them, he said a few words on their cosmological

animal, the Cosmic Tiger, and they shuddered with fear, as if the

Cosmic Tiger had passed by right outside. He spoke of the Cosmic

Tiger's paw print, asked if they had seen it and they said they had,

and he asked if they could point one out to him but they said they

could not, for they saw it in their dreams, they saw it in their

visions. And then Comrade Sunray raised his voice in that hot hut, in

that village where was approaching the time to flee because a UN

vehicle was about to drive on by, he raised his voice to say,

“Because the Cosmic Tiger's paw is gone...but we are still stuck in

its paw print—we inhere almost wholly in its paw print, and from it

we are unable to rise...but now we need to rise...” Then a

long silence ensued as the frightening words showed them the way out,

the way free, but which they knew could not be taken with ease.

Comrade Codebreaker Alpha went outside the hot hut, took from the

field a cow-herding stick, and drew in the dust a map, a very

detailed and meticulous map, and Rolpa fighters stood around it so

that the wind would not blow it away, and it remained intact thus.

“Those who follow this map,” he said, “will become Tharu

Maoists—more than just Tharus.” And at night the Maoists

waited by the X-mark on their map, and hordes of Tharus from the

village came to join them, with

the word “freedom” freshly pronounced by their parched lips,

they came, they came dedicated and angry, and they shared shy smiles

and waited for instructions, and dreams came, and new visions of

utopia were painted out as art that looked like their own, and they

watched wide-eyed and paused before the canvas and then painted more,

and a poetic one among them stood up in the middle of it all and

looked at all the diversity of the Maoist faces with colorful paint

smudged and half-wiped on them and called all of them “the People's

Army.” And sometimes a tiger rustled by in this part of Nepal, its

blazing orange hide seen passing amid the bushes by moonlight by

half-open eyes half adream, but they had no fear of what they saw,

not even of a tiger, at least not then.

At

the end of the training of the Tharu Maoists, when Cosmic Tiger

nightmares had been swept away from their minds, their cosmology was

now more or less erased, after the head comrades through much

deliberation and study had tried to comprehend all of it. They were

then stood before a painting which Comrade Dawn had made which was

the final painting of sorts to guide them, and it was for the first

time in their training a painting which was not “impressionistic,”

so to speak, with style and brushstrokes exuding from the canvas, but

a “realistic” work depicting none other than Chairman Mao

himself, and not the one that Comrade Dawn had seen in the college

dorm rooms of many a privileged student, but one in which Chairman

Mao was humbly working with the people, crouching down and helping

them out with something, on a farm which looked to be bustling with

activity, and it was the people which were key there, people

with stern looks and concentrated faces, they whose minds had

developed the will to work for the cause of the poorest of the poor,

they who wrote by the bright and great maobadi batti their

ideas and tactics without fatigue, never once pausing to reflect on

the raindrops falling from the canopy despite their appreciation of

beauty, for from then on it was people who mattered to them

more than nature did. And because they pored over that painting, the

face of Chairman Mao never left the minds of the Tharu Maoists; it

became a face they saw in their dreams, it became a face they would

always recognize. But the point was at first to get familiar with

it, especially for the fact that the face's features were

different from their own, looked foreign to them, different from all

the faces they had seen thus far. This foreignness did not matter; as

Comrade Dawn always insisted, they were united by something beyond

their faces and bodies. She called it a wheel of Revolution, not a

face, not even a body, a wheel of Revolution: that was the

main thing to keep in

mind, she said. An ever turning wheel of

Revolution which took life

to the firing line for years and years, which caused the supreme

vigilance of the best of them to get better and better day by day. A

wheel also turned by the anger-filled intensification of their

articulations, turned by shouting angrily before Comrade Sunray when

he dared to play “devil's advocate” with them sometimes, just to

fathom their thinking, their major points of debate. And he narrowed

his eyes during these great debates when the wheel of Revolution's

turning was winding down; he was looking to see if something like a

capitalist's core had rotted inside them, as it should have done.

Then one day it happened, in the dampness something rotten fell out

onto the jungle floor and he heard its thump and confirmed what it

was, and so the training was well and truly concluded. Before burning

her notes on the newly-trained Tharu Maoists, Comrade Dawn pieced

together everything they had said about the Cosmic Tiger and their

cosmology: she found out that they believed the Cosmic Tiger was

placed before a cave to guard a flame; it was all metaphorical, but

this much seemed to her like the concrete seed of the whole

cosmology. She took jungle shortcuts, feeling like a kid again

running along grassy shortcuts she knew well, down to the cave they

whispered of. It was glowing at the hole, there really was the Cosmic

Tiger's paw print outside it, and a growl or a rumble issued from

deep inside it when she snapped a twig, as if lightning that night

had led to thunder far far away. She readied her gun and wanted to go

in the cave and kill it but was too fearful to do so, too fearful to

disturb a people's once-beloved cosmology. So she turned back to the

cause instead and tried to forget that it was there.

The

Maoists sat by fires, their souls camouflaged in the night's

darkness, stared at fires, planning and otherwise, but never at that

moment did questions arise, doubts about the cause, for they had

nothing to look back on except empty huts and village kerosene

lanterns going dry and farmer-parents out on barren fields never to

come home and be fathers and mothers to them, but always carrying a

disturbing totem, a disturbing heavy sign hung around their necks and

eyes helplessly leaking fear, with their little joys exercising

control interspersed with bad jokes, with their thinking about

marriage for souls that did not want or need it, as dreamy friends

yearned to go abroad, squinting at a far far away safe place. And in

that moment, that rainy night in Rolpa, one simply did not know when

the Maoists would come and kill, or at least intend to, because one

was not yet on their side and so one was to be considered the enemy.

And the supreme chance, when the bullet narrowly missed the head,

went into the mud wall of the cowshed, the chance to escape, and then

to join their forces, if for nothing else than for the need to

survive those bullets speeding in here and now, and, taking guns from

their wild hands, allowing oneself to be “recruited” in the midst

of battle, in that wildness and desperation, in the line of deadly

fire, when, with a thundering voice saying “STOP!” to the old

life, a new life was discovered, and all the ones that had oppressed

and discriminated suddenly became “class enemies,” with a

distance coming in between, a No-Man's-Land coming in between never

to be inhabited. And “fire!” they said, “FIRE! FIRE!” at

the souls they had always seen and been with, but always with a

No-Man's-Land in between, and that showed the appeal of these Maoists

of Nepal, that they had seen and felt the No-Man's-Land in between

lives, whether in urban places or rural, whether between fathers and

mothers or daughters and sons, between all of them, everywhere, the

No-Man's-Land between people the Maoists of Nepal had seen. Then

something unmanly grew upon that No-Man's-Land, like when at the womb

when the late daughter grew, comfortably deafmute and blind with no

relatives to judge her, then, when daughter was being built by mother

and mother was being built drop by drop of breastmilk by daughter,

and there had then been only peaceful coexistence in their world

before the ancient parental totems had stood large in swirling desert

sands in dreams, real talk had been there about the sheer

poverty which was to surely come, about the thoughts of suicide

camouflaged but no less there behind it and beneath it all. And after

the battle was fought, that night in Rolpa barracks with rain, there

had been shared as many unspoken stories as spoken ones—about who

had madly killed his or her own family, who had spared the witches in

their village huts, who had done what, where-when-and-why—these

unspoken stories had passed between eyes, how unspoken, life had

changed since the daytime when the People's Army had come, and the

high felt at the split-second decision to join that army still flowed

through in the veins, like the high experienced during drunken

card-games in the Rolpa village life left behind, that village of

class enemies now dead or gone...And it had been that card-game high

that so intensely came to the fore in the depths of these

battles—because the war had all been, indeed it still was, full of

youth, so full of youth that got high in the gamble.

Even

the gun battles with the police over control of the village were

completely youthful and had been taken up by the Maoists as a game in

comparison with the larger formulations at stake. These larger

formulations were presented such that the fighters could be as very

much involved in them as the head comrades were. They were heard loud

and clear, after silence fell in the post-battle ghost-villages, also

because the fighters had found a way of talking properly, inspired by

snippets in the newspapers they had tried to read prior to the

insurgency, and also by playing around with the “sign clusters”

that constituted the bulk of the content of every map and meta-map

they had used: the temple, the police-station, the patrolling route

of the police, the river, the village, the trees—the supposedly

“lowly” fighters could make elaborate village-stories out of

these signs, and they even shared such village-stories with Comrade

Codebreaker Alpha excitedly. Sometimes there surfaced in the jungle

UN reports on villages in Nepal, somehow these reports were brought

into the jungle-world, and the fighters all knew to engage with the

reports quite tactically, by evaluating in which

places the UN had not gone far enough in its

description-writing and data-collecting, and hence had failed to

bring development and its language everywhere in Nepal, and

so deducing that these places could be more receptive to the Maoist

insurgency. And so, even as early as the Mugling incident, a

“movement” was developing which emphasized use of the head more

than use of the gun. It was widely believed that powerful people

would listen if the right words were used. Given this newfound

faith in the power of words, in the deepest and thickest of jungles,

where it was impossible for even the most determined of police to

follow on account of their rifles getting tangled in the thicket,

journalists were invited, journalists with slender pens carried in

back pockets, not only to witness Maoist training but to talk to the

fighters, to use interesting words which the fighters could then pick

up and use themselves. And some of these journalists brought along

their laptop computers and Comrades Codebreaker Alpha and Sunray

stared at them till their batteries died, with the other fighters

crowding around these two, who then spoke of the raging rivers of

Nepal that the fighters knew so well, while being

critical of the mean feat of government injustice due to which

the rivers became supplies of electricity to urban areas where people

used such fancy things as laptops, while villages remained without a

single electric bulb to brighten their homes. The fighters, in the

past as idle villagers, had often gone to the raging rivers flowing

by, realizing the promise of electricity all too well--until it got

dark and they had to walk back to unlighted homes, without having

figured out how to make electricity as those big nondescript

hydropower buildings did, when they were humming with activity, those

big hydropower buildings around which the middle-aged village men

were known to linger to the point of madness, sometimes even carrying

their crying infant children there to show the only light bulb alight

for miles and miles. The two head comrades hoped the fighters would

see these urban computer-users as enemies, and, indeed, they did

succeed in establishing an image of urban life, but it was never

clear whether, in the fighters' minds, this was a good image or a bad

image. But no matter what the head comrades said, the fighters might

really have thought that Kathmandu was full of well-lit wide roads

and glittering skyscrapers, and that longing look towards a city

became an enduring problem for the insurgency, whenever the twinkling

dots of city lights were passed by on a patrol close to a city, and

the fighters looked out to them longingly, longing for at least a

taste of what it was like over there, in a big city life that

beckoned...

With

the regular journalists came a reporter-without-borders who wanted to

cover not so much the training and the education sessions but the

People's Army “in action, in combat” as he put it. And the casual

way in which Comrades

Sunray and Codebreaker Alpha agreed to this request made Comrade Dawn

rage: “We have become too comfortable that combat between us and

the police is inevitable. Too complacent about lives being lost! As

committed as I am to this movement, I never think that we should be

so casual about Nepali people getting injured or killed!” Even

though Comrades Sunray and

Codebreaker Alpha tried to explain to her that they would use the

material of the reporter-without-borders “strategically” and “in

the long-run,” Comrade Dawn was thoroughly disapproving and came

close to insinuating that they would one day reduce themselves to

staging fake battles for the sake of journalists. Though

reporters-without-borders was, in a sense, the kind of “organization”

that would be an integral component of the utopia that she imagined,

she did not want the movement to go down this road in which the

fallen would be totally ignored. Thus, on her insistence, a

handwritten note was sent to the reporter-without-borders claiming

that the Maoist leadership just did not know whether

or not a gun battle would actually occur: “The Maoist

movement is highly sensitive to the day-to-day developments in the

People's War and cannot say for certain that there will be a future

situation where a gun-battle will be fought by the People's Army

against any outside forces.” Despite this disappointing turn of

events, the reporter-without-borders came, dressed in khaki and a

safari hat, this foreigner who, that very afternoon, had half-eaten a

good lunch at a good Thamel hotel, came with the still-preserved

childhood habit of walking into a forest in the wilderness of remote

Nepal as he would walk into a grove in a small Western town, without

regard for paths or proper navigation, and still never get lost or

ever feel uncomfortable or indeed look out of place. Then a Tharu

Maoist could not help but feel rising in her the deeply engrained

Nepali hospitality towards all foreigners, who, with Visit Nepal '98

stickers on their laptops, sat down to witness that Tharu Maoist

perform a traditional dance, to their utter delight and firm belief

that they were witness to a “beyond borders” event, given the

almost universal love and almost spiritual oneness projected in that

moment. It was beautiful, and it was something the UN worker in his

small cubicle would never get to see, never see precisely because of

his workplace alienation that the Maoists wanted to address, but

which the UN strongly defended as necessary. And that Tharu Maoist

dancer danced well into the night and nobody wanted to sleep, that

gaggle of borderless foreigners much too excited by this visit to

these violent parts of Nepal. A goat was carried in and dramatically

beheaded right in front of them, a goat to be cooked for a borderless

feast, with hot goat-blood squirting all over the place, painting the

ground and the leaves in a red color that glistened with the light of

the fire that was busily burning away. And there and then, Comrade

Dawn took all of this in: the twitching dead goat, the blood-red

hands of the fighters tending to its insides, the blushing

foreigners, that authentic Tharu dance...and it was so overwhelming

to her, that gap between what she used to see and what she saw now,

all these things that today consumed her world, her mind, her

work-day, the Great Red Project underway, the gun-battles in the

minds of these foreigners looking for a thrill—she closed her eyes

because things were approaching an end-point for her: the project and

the pain were ending. And she saw these things now, she simply saw

these things: a shred of a policeman's uniform stuck on a bramble, a

map of her life, and a far more generalized meta-map of where she was

right now, and what she was doing right here, and she opened her

eyes...and it was gone...she didn't see anymore, she thought...she

was...she was lost...

A

shred of a policeman's uniform stuck on a bramble, and everybody saw

it, grew alert that the police were close by, and guns were raised

and aimed at the bushes, beyond which a rustling could be heard, the

sounds of someone attempting to negotiate wild terrain, to come to

terms with terrain which had been trained for, with lessons crowding

the mind, strings of theories that attempted to explain these chaotic

twigs and leaves going over their heads, and the policeman zoned out

with far-off-looking gaze despite the presence of powerful members of

the force, zoned out to a village home far far away where were

waiting a wife and kids, waiting by the maobadi batti he had

brought home on one occasion, as outside spread the opaque blackness

of night, the moment ripe for political hostility, the rage of the

fighters in the stifling humidity of the night very hard to contain.

And ignoring their fearful prayers a loud gunshot ripped through the

night, and the policeman was brought back to attention, to the

classroom where lessons in guerrilla warfare had been taught, to the

powerful policemen staring at him, at how zoned out he was, how far

gone. Or perhaps it was something else in its entirety, as his limbs

weakened and blood seemed to flow endlessly from a wound, and he

stumbled to the ground, more shots ringing out all around them, then

to be even less alert and more zoned out than ever before, lying face

down in the jungle mud when his heart, in truth, was far off in the

distant village where they were waiting for him to return. But he

couldn't even stand up now; his blood had all poured out from his

wound. “STOP,” had screamed the teacher-police, “STOP zoning

out, STOP daydreaming,” but that was how village days, not

even that long ago, had been spent, so that it was difficult for him

to stop these things, even as a pain was coming on now, a pain which

he had never felt before, an all-too-intense pain which finally did

pull him away from zoning out and daydreaming. But he was helpless;

what he had loved was torn, a shred dangling from a bramble, and

everybody else had fled. The sheer size of the People's Army had

overwhelmed everyone else; he alone couldn't move from the floor, nor

move in the classroom where he sat frozen most of the time, when came

another “STOP” shout, another shot, and it was done now, he was

gone, and never had he thought more of his family and village before

that moment at Raniban, before his eyes closed—merely two hours ago

he had been sleeping and dreaming of them in the barracks, and now he

was gone...

And

in the immediate aftermath of the Raniban ambush, Comrade Dawn began

to inquire about ways of leaving the Maoist insurgency. At first she

was hopeless, for she realized there was no way out of the jungle:

“How can I go back to Kathmandu when all I have is this Maoist

uniform I wear?” The insurgency had begun to seem to her, trapping

as it did its subjects in the jungle, authoritarian in nature, not

yet in the sense of actually having an authoritarian leader

insisting that she stay in the jungle, but definitely having opened

up the space for such a leader to emerge, given the way of life they

had chosen, their inability to escape from it. So she took a walk in

thought, in deep thought, about these things, about structures and

systems and agents, and her walk became long and non-linear, yet it

was so very fruitful for her to think and problematize the general

operation of systems, specifically ones which were more territorially

confined than chaotic and randomly expressive in vast and accessible

empty space. And so she walked, and it was never clear whether she

had actually arrived at the flatlands of Thimi in Kathmandu Valley or

whether she had envisioned her arrival in her madness, in her brain

now with a rusty “Disturbed” sign hanging at its entrance gate,

its borders lined by intensely bright Deepawali

decorations hanging from unpruned synapses that had begun to encroach

a vacant ventricle, with loudly buzzing bush insects wildly flying in

circles, multicolored but about to burn out to black, also causing a

vague but persistent ringing in her ears that she hadn't heard until

after the deafening sounds of bullets and bombs faded away. She

arrived fully dressed in Maoist uniform, and yet, perhaps it was good

fortune and nothing else, or simply a vision, nobody

made a scene, nobody went looking for the police, and she in her now

free, non-linear mind and life looked around, at a street-dog going

through a garbage bin, a political taxicab going by, blaring its

messages about a strike or some such event the next day, a

well-dressed newlywed smoking a cigarette, and then lightning far in

the flatlands, raindrop rounder than coin, white-noise still

scattered in the distance, clothes heavy on the clothesline, plans

heavy in the pipeline as heavy women waited under the closest roofs

to dry, looking at the sky...

The author hasn't added any updates, yet.

$15

The first ten readers will get insight into the writer's thinking regarding the structure, plot and characters in the book. These insights will be provided through short notes and placed at the end of the book.

Includes:

$20

All readers will receive signed copies of the book.

Includes:

$40

Get 1 print copy + 1 for a friend, plus get mentioned by name before the epigraph.

Includes: