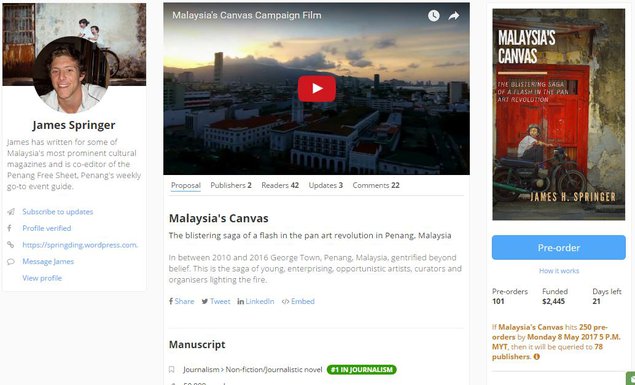

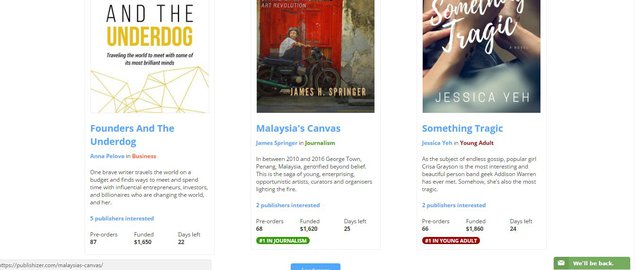

The blistering saga of a flash in the pan art revolution in Penang, Malaysia

In between 2010 and 2016, George Town, Penang, Malaysia, was gentrified beyond belief. This is the saga of the young, enterprising, opportunistic artists, curators, and organizers lighting the fire.

Ended

In February 2014, an international colony of young, freewheeling, and footloose artists held a group exhibition that would stand as a pivotal turning point for the future of George Town, Penang. It was an exhibition destined to make the artists household names, infamous for boldly swinging into parties and installing challenging art onto South-East Asian walls. It would also spell the transformation of George Town into a worldwide destination, a city rising from backwater ashes to heights shared by heritage, culture, and cosmopolitanism.

Enter James H. Springer, an expatriate journalist heavily connected to George Town’s countercultural artistic scene and uniquely placed to ride the wave of gentrification alongside the artists on their own terms. In this intensely personal exposé, Springer documents the life and times of the artists during the period of 2010 to 2016, telling the story of gentrification through their own influential experiences. Through childhood memories, artistic inspirations, fluctuating relationships and artwork – learn how these young artists lay a new path for George Town going into unpredictable times. During what could arguably be described as Malaysia’s most troubling political era, Springer describes how the flourishing of art in George Town gave its population a much needed respite from federal government tomfoolery. In addition, it gave Penang State – as a nexus for the opposition party’s Democratic Action Party – a leg up in economic prosperity, creating an unheard of level of opportunity that would either be capitalised on or squandered.

A mix of journalism, storytelling and unheard truths, Malaysia’s Canvas lays bare the reality of being an artist in a developing country and the change it can inspire - for amateurs or professionals interested in socio-cultural development in South-East Asia, with no holds barred.

Foreword by Rene Feddersen

Rene Feddersen personifies what it means when people say we have a universe inside of us. He is tall (6 ft. 7”), full-hearted, and resonant. So, if not universal in proportions then certainly mountainous. Rene is a quarter Thai, German, Indian and British, speaks all his ethnic languages fluently, and resides in Thailand with his wife and baby girl. Before running Thailand’s premier courier service, Rene came into art through his prestigious gallery in Bangkok, during which time he amassed a considerable collection of South-East Asian art. His foreword will provide invaluable context when considering George Town’s art scene in South-East Asia.

Prologue

A brief history of Penang and George Town as a British colony. Also, defining the collective term for a group of artists ('a colony of artists') and some examples throughout history of how artistic communes have helped develop an area. This is considered with the aim of understanding that gentrification is not a new phenomenon and that this book merely tries to document the specific transformation in George Town, rather than realising the process as a whole.

Part 1: Primed – 2014

Chapter 1: Malaysia’s Canvas starts on the day and night before the opening of Think About It, an exhibition regarded as the anticipated follow-up to Hin Bus Depot's opening, which featured unique art pieces by Ernest Zacharevic – George Town's prodigal-mural-son. George Town will be described in all its fresh artistic glory, setting the scene mid-way through the proposed timeline. Some of the key artists used throughout the book are introduced as exhibitors in Think About It (Bibi Chun, Kangblabla, Renny Cheng, Tan Kai Sheuan, Low Chee Peng and Gabriel Marques). Tom Powell is introduced – also an exhibitor – now a prominent artist in George Town and Malaysia, who started his artistic career in Penang.

Part 2: Blank Canvas – 2010-2012

Chapter 2: How was George Town before the art boom? It needs stating that George Town was not completely barren of art before 2010. In fact, there was an underground scene of artists, collectives, institutions, and organisations dating back to the 1800s. Due to Penang’s eclectic cultural development, iconoclastic buildings adorning its young shores drew artists, artisans and craftsmen – most notably, from China. Groups grew through this interaction, such as the Penang Art Society, the oldest art society in Malaysia today.

Chapter 3: Despite art beginning to find its voice in Malaysia, artists faced an uphill battle for exposure in an industry dominated by a Western market. The first Henry Butcher auction held in Kuala Lumpur, 2010, serves as the centrepiece behind a comparison between Malaysian and Western artists. The reasons for the stark differences in value are explained through historical and political restraints, not to mention the economy, in Malaysia.

Chapter 4: Taken from journal entries, this chapter records the experience of Chinese New Year in 2010. In particular, James notices the difference the vibrant festival strikes with a city usually beleaguered and struggling with atrophy. It switches to personal accounts of the lives of artists introduced in Chapter 1 living in George Town. As well as their living conditions – mostly squatting – comparisons are drawn between the amount of work available to individual artists. With the daily lack of artistic drive in George Town, it seemed that paid work was not a matter of what you knew but whom you knew.

Chapter 5: A consideration of the opportunity to study art in Malaysia for aspiring artists. It looks at Renny Cheng and Tan Kai Sheuan, who both studied art in Taiwan, culminating from a trend of local artists – or even students of any discipline – studying abroad. Using examples from artists Sliz, Bibi Chun and IMMJN, the reader is told of the obtuse road into art taken by those who studied in Malaysia. As a result of this, the significance of Penang’s/Malaysia’s art mentoring is highlighted.

Chapter 6: A personal account leading to the inaugural George Town Festival from James' first introduction to Joe Sidek, the festival director, in 2009. This chapter assesses why Joe was the best person to organise the festival, considering his experience in the arts and the difficulties he encountered. A description of the George Town Festival and its aims, comparing the media’s portrayal of it to the reality. After the festival, a consideration of the most vital question: who was the festival for? And, would it serve to aid George Town or destroy it?

Chapter 7: Departing from George Town and Penang, the focus moves down to Kuala Lumpur and into the lives of Rumah Studio’s founding fathers, Bibi Chun and Sliz Supertramp. Sliz and Bibi recount their upbringings and paths into art including their inspirations, mentors, and education through their first artistic discipline: graffiti. Includes personal accounts of their lives leading up until 2011, and shows how they navigated a splintering graffiti scene, focused more on fine art, and finally made their way to Penang on the heels of Ernest Zacharevic.

Part 3: Incubation – 2012-2014

Chapter 8: Introduction of Ernest Zacharevic from the tail end of 2011 explaining his background and reasons for coming to George Town. Why did he use children as the subject for his murals? How did he come to start a series of revolutionary murals? What was the local response to a foreigner painting on their walls? Ernest describes whether he thought his murals would ever become as successful as they are. Always the stoic, Ernest enlightens us to the reality of the contradictory aims of art; aims of the artist vs. aims of the people and State. His arrival naturally leads to the mural explosion in preparation for the 2012 George Town Festival – a body of work entitled Mirrors George Town.

Chapter 9: Much like in Chapter 6, this chapter reviews the George Town Festival 2012. As well as noting the event schedule and the caliber of acts involved, this will again compare the media’s portrayal of the festival with the reality. It will also serve as an opportunity to determine how far the festival had progressed compared to 2010. Following on from the George Town Festival, this chapter describes the personal experience of RESCUBE – the first exhibition conducted in an abandoned shop house, which later turned into a clubbing party. Which was more effective at bringing art to the people: the growing machinery of the George Town Festival or organic exhibitions organised by a colony of artists, curators, and collaborators? The answers are discussed from the perspectives of RESCUBE’s artists and organisers.

Chapter 10: After the George Town Festival of 2012, Malaysia's Canvas reviews the status of George Town in the local and international media. Had the George Town Festival, in the past two years, raised the city’s profile or even given it life? Had it provided artists with more work? What were expectations for the festival, now in its second year? Then, focusing on the national dilemma of censorship, we review whether censorship laws had become more stringent, providing examples of it continually plaguing creative expression, and what it meant for art and artists in George Town.

Chapter 11: 2013 brought with it the first clash between artists’ works and the media acting as the public’s mouthpiece. Ernest defends accusations by national publications that he was ‘reviled in Johor Baru,’ that he would ‘hurt tourism,’ and that he had incited ‘Penang’s chagrin.’ Rumah Studio recount their experience of a mural misinterpreted by the media and subsequently destroyed. After the calamitous General Election, artists give their thoughts on the politicisation of art and the extent to which they became more political questioned. Did the George Town Festival react creatively to the rigged GE? With all its accumulated influence, could it or would it stand up where individuals could not?

Part 4: Sold – 2014-2016

Chapter 12: The anguish continued throughout 2014. Malaysia’s dubious status quo suddenly erupted, spewing disasters in every direction: disappearing aeroplanes, floods, earthquakes, inexplicable censorship, protests and a trend of debilitating international headlines that would continue for years. While undoubtedly distressing, these events provided reams of inspiration for discerning artists, as well as a frame of reference for any potential clients previously unaware of Malaysia. This chapter details the results of Think About It, determining whether the artists involved found it useful. Artists – local and international – describe how their art began progressively taking more inspiration from Malaysia’s situation, culture and environment. They discuss whether artists should curb expression in compliance with public sentiment, based on further complaints sourced from the national media.

Chapter 13: It was in 2015, after the tumultuous start to the 1MDB scandal, that George Town’s art scene began to show true dynamism. Comparing three events – the then permanent fixture of the George Town Festival, the high-end exhibition Hypocalypse hosted by base2, and the Urban Xchange Festival – we learn of the depth of art in George Town as well as the breadth of events to choose from. In the words of the Penang Free Sheet – the island’s new guide for events taking place each week – there was no excuse for saying ‘nothing ever happens in Penang’ anymore. Did artists involved jump at the opportunity to use art as inspirational political statements? Alternatively, were censorship laws too intimidating, despite Penang’s Chief Minister Lim Guan Eng flaunting the DAP's belief in freedom of speech?

Chapter 14: What had George Town’s art scene become? How much of it was 'inspiration' and how much of it was 'raw business'? Did each, or any, of the artists have the feeling they had found their 'voice?' What had their motives behind pursuing art become? Where did they see Penang's art market going? With the influx of prominent collectors and an exodus of retired expatriates, did this mean art would take the next step into sophistication? How did the property development boom aid or restrict the artists' capability to continue their artwork in George Town?

Chapter 15: By 2016, George Town's art scene had begun to snowball, meaning it had gained enough traction and mass to grow continually, without effort and, arguably, much thought. Is this true? This chapter will consider the spread of contemporary art culture onto the mainland in places such as Butterworth (Butterworth Fringe Festival) and Muar (a mural project that used Penang's success with murals as a template for development). Where would the artists, and George Town's art scene, go from here?

Epilogue

During the specified period, what does the example of George Town's art boom mean for art in the world and the role it plays? Perhaps the answer lies in a fine line between two contradictory realities. Art – as it always has – remains an inspirational and influential medium for people looking to break from a certain monotony in life. On the other hand, George Town's example reveals a fixation on the business side of art, and how monetizing art can be detrimental to a place and its people. In a world where the main failure is being left behind, should not something as powerful as art be handled with more poise and sensitivity? James think that it should.

Although set over six, helter-skelter years in a small, South-East Asian city, Malaysia’s Canvas has a universal appeal and will resonate with those who are interested in or actively involved in art scenes and its impact on any city experiencing globalisation and gentrification. A tropical, highly-spiced, Malaysian variation on an age-old theme of art, artists, patrons, and curators reacting to and engaging with rapid social change, whether in Renaissance Florence, present-day London’s Shoreditch, or New York’s Lower East Side.

More importantly, it tells the story of those who have – as yet – not been recognised as the driving force behind George Town's promotion onto the world stage. Through personal accounts of artists, readers in countries with emerging or established art markets in South-East Asia (for example, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand, Cambodia, Indonesia, and Hong Kong) will discover the genuine process of George Town’s gentrification through art. Not just for casual readers, this book is also a valuable tool for researchers, academics, students, or even armchair professionals who concentrate on art in the South-East Asian region.

Let us not forget that political strife has also put Malaysia onto the world stage, as we see international publications (The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Guardian UK, The Telegraph, and The Economist – to name a few) reporting more frequently on Malaysia's position in the world. Currently, Malaysia is typically viewed through a prism of dirty politics. This book will present Malaysia to the world through the more positive story of George Town's art scene and its artists.

George Town itself is, also, no longer an unknown entity. After being voted a top destination for its vibrant food scene, rich heritage, and potpourri of cultures by publications such as Lonely Planet, the city has impressed itself onto minds of people around the world. However, I would argue that the raw foundation of George Town’s recent international exposure is in its artists and their art.

What better marketing plan - for an author - than word of mouth! Living in the city the book concentrates on and being in regular contact with a population still miles away from the artists' stories, I can say that I am on the ground and able to promote myself in the region.

Read an author interview published in The Deck, a funky online portal for all things fashion, art and culture, based in Kuala Lumpur, at https://thedeckzine.com/malays...

I have contacts within Malaysia's largest book stores (Popular and MPH) as well as Malaysia's biggest publishing house Mongoose Publishing, so these are easy avenues to push sales of the book.

In Penang State, I have relationships with the director of George Town Festival - a huge platform that once a year holds the State's only international festival - and notable organisations such as Penang Heritage Trust, Penang Global Tourism, Think City, and TedX Malaysia, which constantly support events such as the Penang Literary Festival. Such avenues, for me, are easy to tap into and have proven to be powerful marketing organisations.

On a personal note, being a co-editor of the Penang Free Sheet has allowed me to create relationships with many types of businesses, institutions, and organisations. In the world of big cities and glittering skyscrapers, Penang State and George Town fall very short. But, the institutions charged with developing the State - such as the ones mentioned above - are powerful tools for nation-wide coverage.

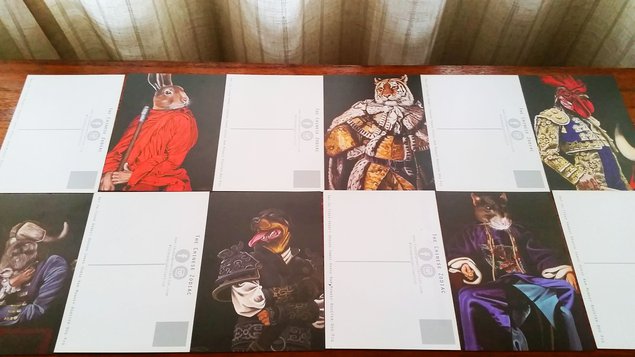

12 postcards by Tom Powell:

Bonus Art:

Numerous books currently on the market cover the subject of art gentrification in countries all over the world. It is a process that has occurred throughout history, and has always been a point of interest due to the unique and specific factors in its place and time. While the examples below give a good indication of this book’s attraction, they still do not contain the distinctive flair and intense realism that Malaysia's Canvas is bound to bring to its audience through the perspectives of real artists as well as Malaysia’s exotic setting, vibe and rhythm.

Jaret Kobek’s Never Let It Stop: A Novel (Viking, 2017): As a fictional example, Kobek’s novel clearly identifies the mood and dynamism behind artistic realisation and the life of an artist living in a city off the beaten track. While his protagonist slowly slides into art, Kobek’s descriptions of an underground life balancing work, drink, drugs, and sexual excess perfectly exemplify a part of Malaysia's Canvas when those involved in George Town’s underground artistic routes were more concerned with ‘playing’ with spaces, ideas, and events.

Aaron Shkuda’s The Lofts of Soho (University Of Chicago Press, 2016): By documenting the physical nature of gentrification – the transition from empty space to artist’s enclave to affluent residential area – Shkuda rings a similar bell to Malaysia's Canvas but with SoHo in Lower Manhattan. Most importantly, he goes into great deal about conflict between residents and property owners, as well as how artists eventually lose control of an area and its development, for good or ill. The roles of not only artists but young curators, creative directors, organisers, and facilitators in George Town’s gentrification, and the need for them to be taken seriously, is an important theme of Malaysia's Canvas.

Mark Gibby's Street Art Penang Style (Self-published, 2016): Published in Penang, Street Art Penang Style is the best – and most current – in-depth visual record of the different types of art found around the State, complete with small artist profiles and pictures of their work. However, it lacks the story behind George Town’s artists and its gentrification, which Malaysia's Canvas aims to tell.

Malcom Miles’ Limits to Culture: Urban Regeneration vs. Dissident Art (Pluto Press, 2015): Using examples spread over the UK, Europe, and the US, Miles succeeds in delivering a thought provoking assessment of what creativity means in cities more interested in commercial profit and controlled urban planning. Spanning a period of almost half a century, Miles challenges notions of the ‘creative class’ and ‘creative city’ by arguing that they largely masked certain urban redevelopment programs, attributing them more to gentrification and the elimination of urban dynamism that it entails. This book’s basic tenant – how to unmask the vested interests behind a ‘cultural’ urban agenda – is a brilliant example of the political, economic and social interests at work behind steering the development of the arts in George Town.

Faedah Totah’s Preserving the Old City of Damascus (Contemporary Issues in the Middle East) (Syracuse University Press, 2014): Proving that gentrification is not only an issue in the ‘Western’ world, Totah details the trials of neoliberal urbanism and the competing views of developers, government officials, and long-term inhabitants over the use of urban space and historic neighbourhoods. In Malaysia's Canvas, through the author’s contacts in government, heritage trusts, and development corporations, these issues will be integral in determining the cost/benefit analysis of George Town’s gentrification. There is also the great similarity of both Damascus’ old city and George Town’s heritage zone being under UNESCO protection, a designation that it not always solidified and can be taken away if not honoured through heritage protection.

Jonathan Letham’s The Fortress of Solitude (Vintage, 2004): A fictional account of Brooklyn in the 1970s told through the eyes of a young, motherless boy. Letham touches on certain parallel plot ideas such as race, gentrification, graffiti, tagging, and music, but his book’s most valuable example lies in his up-beat prose and raw storytelling. While not a work of fiction, Malaysia's Canvas aims to emulate Letham’s writing style to keep the novel hard-hitting and punchy.

Rebecca Solnit and Susan Schwartzenberg’s Hollow City: The Siege of San Francisco and the Crisis of American Urbanism (Verso, 2001): Solnit and Schwartzenberg paint an intimate picture of artists, activists, non-profit organisations and the poor exiled from San Francisco’s developing areas. They also document homogenisation of the city’s architecture and erasure of its sites of civic memory through distinctive characters and locales academically researched by Solnit, complemented by Schwartzenberg’s photo-essays. These are prevalent issues in Malaysia's Canvas, and Hollow City reveals how a story can be woven around pictures of artwork and the scene.

James has been writing on a free-lance basis for the Expat Group for 5 years and other publications such as Penang Monthly and Esquire Malaysia. He concentrates on cultural and political issues in Malaysia, concerned with how developments in these spheres will affect his second home, George Town. Having cultivated friendships with artists, politicians, restauranteurs and entrepreneurs, James is poised to tell the world of George Town's recent artistic explosion - a city he has called home for the last 7 years. James has personal relationships with key figures behind the city's gentrification – including the George Town Festival’s director, Joe Sidek, and the city’s mural-son, Ernest Zacharevic - and enough trust between them to honestly reveal the convoluted and - sometimes - warring dynamics behind putting a previously unheard of city onto the world stage. As well as that, James has seen the city itself morph from an ugly, decrepit, abandoned city full of charm and character to a rapidly glistening, lively place that is in danger of losing much of its coveted heritage. As co-editor of the Penang Free Sheet, he is conveniently placed to comment on the rise of art, exhibitions and events that currently encapsulate the city’s new life.

250 copies • Partial manuscript.

Anaphora Literary Press was started in 2009 and publishes fiction, short stories, creative and non-fiction books. Anaphora has exhibited its titles at SIBA, ALA, SAMLA, and many other international conventions. Services include book trailers, press releases, merchandise design, book review (free in pdf/epub) submissions, proofreading, formatting, design, LCCN/ISBN assignment, international distribution, art creation, ebook (Kindle, EBSCO, ProQuest)/ softcover/ hardcover editions, and dozens of other components included in the basic package.

500 copies • Complete manuscript.

Blooming Twig is an award-winning boutique publishing house, media company, and thought leadership marketing agency. Based in New York City and Tulsa, we have represented and re-branded hundreds of thought leaders, published more than 400 titles in all genres, and built up a like-minded following for authors, speakers, trainers, and organizations with our bleeding-edge marketing strategies. Blooming Twig is about giving the people with something to say (“thought leaders”) a platform, walking its clients up to their own influencer pulpit, and making sure there is a like-minded crowd assembled to hear the meaningful message.

Bookcity.Co is a self-publishing platform. Offers Manuscript Assessment, Copy Editing, Book Cover and Interior Design, E-book Conversion services.

Bookcity.Co also distributes your printed books, e-books, CDs and DVDs to a wide distribution network, including Amazon, Barnes and Noble, iBooks, Google and many other popular retailers worldwide.

250 copies • Completed manuscript.

Koehler Books is an Indie publisher based in Virginia Beach, Virginia. Our team of dedicated professionals promises you a holistic publishing experience where you'll receive our full attention, collaboration, and coaching every step of the way. We offer two publishing models: a traditional non-fee model for the highest quality work, as well as a co-publishing model that includes creative development fees for emerging authors. Our titles are broad-based and include nearly every major non-fiction and fiction genre.

Mascot Books is a full-service hybrid publisher dedicated to helping authors at all stages of their publishing journey create a high-quality printed or digital book that matches their vision. With comprehensive editorial, design, marketing, production, and distribution services, our authors have the support of an experienced publishing team while still retaining one of the highest royalty percentages in the business.

250 copies • Completed manuscript.

Motivational Press is a top publisher today in providing marketing and promotion support to our authors. Our authors get favorable rates for purchasing their own books and higher than standard royalties. Our team is at the forefront of technology and offers the most comprehensive publishing platform of any non-fiction publishing house including print, electronic, and audiobook distribution worldwide. We look forward to serving you.

250 copies • Completed manuscript.

E.L. Marker™, WiDo Publishing’s new imprint, is a hybrid publisher established to meet the needs of authors in a changing publishing climate. Now, more than ever, writers are seeking a blend between self-publishing and traditional publishing. They want an option that offers the higher royalties and greater control associated with self- publishing, while enjoying the prestige and quality provided by a traditional publisher.

250 copies • Partial manuscript.

Authors Unite helps you become a profitable author and make an impact. We take care of printing and distribution through major online retailers, developmental editing, and proofreading with unlimited revisions. We take care of the entire process for you from book cover design all the way to set up your backend so all your book royalties go straight to your bank account. We can also help with ghostwriting if you prefer not to have to figure out all the steps on how to write a book yourself.

With our book marketing services, you don’t need to worry about figuring out all the steps on how to market a book or how to become a bestselling author. We’ve helped hundreds of authors become bestselling authors on Amazon, USA Today, and The Wall Street Journal. We take care of the entire book launch process for you to help you sell thousands of copies of your book and become a bestselling author.

View case studies here: https://authorsunite.com

100 copies • Partial manuscript.

Bookmobile provides book printing, graphic design, and other resources to support book publishers in an ever-changing environment. Superior quality, excellent customer service, flexibility, and timely turnarounds have attracted nearly 1,000 satisfied clients to Bookmobile, including trade houses, university presses, independent publishers, museums, galleries, artists, and more. In addition, we manage eBook conversions and produce galleys, and regularly provide short-run reprints of 750 copies or fewer for major publishers such as Graywolf Press.

100 copies • Completed manuscript.

Happy Self Publishing has helped 500+ authors to get their books self-published, hit the #1 position in the Amazon bestseller charts, and also establish their author website & brand to grow their business. And the best thing is, we do all this without taking away your rights and royalties. Let's schedule a call to discuss the next steps in your book project: www.meetme.so/jyotsnaramachandran

100 copies • Completed manuscript.

Jetlaunch book design and project management services give you back the hours you need to grow your publishing business. We've done work for John Lee Dumas, Ed Mylett, Rachel Pedersen, Dan Sullivan, Aaron Walker, Amy Landino (Schmittauer), Kary Oberbrunner, Jim Edwards, and many publishing companies. You retain all rights and royalties.

Get your ebooks into the biggest stores and keep the 100% of your royalties. Amazon, Apple iBooks, Google Play, Kobo, Nook by Barnes & Noble and more.

ShieldCrest are book publishers based in the UK who fill that vital gap for talented authors where mainstream publishers are unwilling to give them that chance. We strive for excellence and invest in our authors and are listed in FreeIndex as the number one independent publisher in the UK for price quality and service rated author satisfaction. We publish books of all genres including; fiction, historical, biographies and children's books.

ShieldCrest publishing continues to grow rapidly with satisfied authors throughout the UK and overseas. Our range of products includes paperbacks, hardbacks and digitised e-books in all formats used globally in the myriad of e-readers.

In addition to the above, ShieldCrest provides a complete range of services including book design and layout, illustrations, proof reading and editing. For marketing we offer author web page, press releases, social media marketing packages and many other support services to help both first time and experienced authors get their books into the market quickly and maximise on the opportunities available.

These services enable us to guide our authors through the process as we transform their manuscript into a professional book, which can take its place with pride next to any famous author's book of the same genre.

The staff at ShieldCrest have many years experience in the book industry and this wealth of experience is put at the disposal of our authors.

Our clients include established authors such as Diane Marshall who has been acclaimed as the best writing talent to come from Scotland for years by The Scotsman newspaper, and Prof Donald Longmore OBE, who performed the first heart transplant in the UK and has sold thousands of medical books used by students throughout the world. We also recently released "Martin Foran-The Forgotten Man" by J.R. Stephenson, which features fraud within the police, abuse within the prison service and injustices in the courts and has been featured in the press and on TV.

Chapter 1

George Town’s city streets illuminated under a crisp dawn. Terracotta tiled rooves dusted with dew twinkled in the morning twilight…the temperature sat at a cool twenty-three degrees Celsius in March 2014. For the previous couple of days, the small island of Penang had been shrouded in haze, turning all sunlight into a thick orange miasma, reducing visibility, and triggering a golden glow. Air Pollution Index recordings taken from Universiti Sains Malaysia read 79 points, ironically considered moderate by scientists also commenting on a faint smell of smoke in the air. Stories of asthma patients, struggling under the dense smog, admitted to hospital were met with weary concern.

That morning, after a violent bout of rain cleared the haze, the city lay in clear brilliance. In all four corners, streets slowly revealed their embellishments as the sun rose higher in a cloudless, blue sky. Shadows turned in for the day exposing heritage shop house gables, then decorative pillar heads and roof beams under eaves…further they retreated baring louvre shutters in a rainbow of colours…further still they withdrew uncovering handcrafted green ceramic air-vents. Finally, with the sun close to its zenith, front porches were lit unearthing hand-carved ventilated wooden doors flanked on either side by steel-barred windows. Patio floors bared hand-painted ceramic tiles, granite edges, and granite steps, bridging open drains leading down to tarmacked streets.

Interspersed on walls of these southern Chinese, early and late Straits settlement edifices were George Town’s most recent claims to fame. In the northern quarter 'Kung Fu Girl' was poised climbing, her hands placed on two window coverings on either side of her gigantic body, looming large over Jalan Muntri. In the south-east 'Little Children on a Bicycle' on the corner of Armenian Street and Lebuh Pantai, and 'Boy on a Bike' on Lebuh Ah Quee, interacted with wall installations. 'Children in a Boat' floated above the milky dock waters on a wooden wall in the Clan Jetties. In the south on Gat Lebuh Acheh, 'Reaching Up' showed a boy standing on a wooden chair straining for a window-let just out of reach. To the north-west, 'Relaxing Trishaw Man' relaxed on lime-white, watching life awaken on Penang Road.

***

“Local and foreign artists use art to communicate with society.” – Article in The Star online, March 2014

***

That night, past midnight, before the opening of Think About It, the air was sticky with humidity. Artists, wearing fisherman pants, decorated with tattoos and covered in paint flitted around the cavernous interior of Hin Bus Depot – casually known as ‘Hin’ – the only light source on the quiet street of Jalan Gurdwara.

Inside, the artists' dance ensued as a whirling blind of soft-mutterings and unexplainable shouts – hammering, drills revving with screws balanced between lips, wall plugs thrown from one side to another, and the rattle of measuring tapes retracting. The ornate ceramic-tiled floor was strewn with wires, extension cables, tools – and their boxes – nails and ladders, as the group of artists deftly picked their way from one cluster of activity to another looking for equipment, ideas, wisdom.

The hall was enclosed by peeling, tea-stained, decrepit walls – George Town’s stylish salute to times gone by. These four walls were as much a part of the exhibition as the art itself, in the same way that a celebrity contributes to an event. They sat, above the bottom line, as an added incentive to attract a gushing public eager to see for their own eyes how they were so uniquely repurposed. Hin, in its history as an abandoned bus depository, encapsulated George Town’s rising fame as a living city frozen in time, its decomposing exterior slowly gentrifying to reveal a swan-like beauty; it was given new meaning through purpose and becoming important after being neglected for so long. The public may have seen contemporary art before, but never decorating the interior of a discarded old bus depot.

The artists – Bibi Chun, Kangblabla, Renny Cheng, Tan Kai Sheuan, Low Chee Peng, Tom Powell, and Gabriel Marques – moved in a desperate struggle against time, quick fingers marking the walls in pencil, making frenzied improvisations and minor changes, coming together to create order out of chaos. It was the last great push toward the end of a process that may have taken some more than a year to complete and held a tangible panic.

Top-knots, leather necklace straps, vests, batik shirts, sandals, and flip-flops were slowly being drenched in sweat, fabric turning a darker shade down a spine or chest. Paintings were handled roughly, grabbed from their resting places and flung into the air for a lower grip, finally coming to rest on top of freshly placed screws. It was done with sheer minded zeal, almost a cathartic process of finally releasing pieces that had eventually become burdens. Without exception, as soon as each of the artists hung one of their pieces for the last time, they released a small amount of tension as another worry finally found its resting place, seen in a lightness of step, shoulders relaxing, and the beginnings of a wry, hopeful smile.

The whole night had been fraught with angst disguised under a mask of geniality, banter, and beer. When I first arrived, having had a tacky can of Skol thrust into my hand, the scene appeared social with people huddled around catching up. I joined Tom, Bibi, and Renny in what I assumed was a casual conversation until I realised it had already begun. The set-up was being put in motion through maths, psychology, and discussions on perspective.

On any other evening, such earnestness would have quickly dissolved into beer-fueled frivolity, but an exhibition of this potential is an artist’s livelihood. It was Hin’s second exhibition as George Town’s up-and-coming gallery and came off the back of a revolutionary opening held by Ernest Zacharevic, George Town’s prodigal-mural-son responsible for the mural extravaganza whipping the public in the direction of art. After the opening, whispers had circulated the island containing hushed references to “New York,” a “revival of the art,” and a general feeling that George Town’s art scene was set to explode.

This sort of train is impossible to ignore for an artist, hence the exacted nervousness prevailing that night. There was a feeling of jumping on the stir that Hin and Ernest had created, as well as a slight apprehension of letting the side down. The second exhibition needed to be perfect, if not better than the first, and the artists were making sure it would be nothing less.

After conversation morphed into diligent graft, I moved over to the make-shift ply-wood reception area filled with the entourage. It seemed that all of the artists had a friend or girlfriend present, congregated around a solitary, gigantic amplifier with the front cover torn off revealing black, pulsating speakers. The sound, saturated with base, filled the hall with electronica, psychedelic rock, alternative indie, and the air fizzled. The music, coupled with frantic energy – artists skipping over discarded equipment, spot lights punched in and out of ceiling tracks, woops and cries signalling successes and set-backs – resembled more a steam-punk disco than the setup of an exhibition.

***

“The only people that interest me are the mad ones, the ones who are mad to live, mad to talk, the desirists of everything at the same time, the ones that never yawn and say a commonplace thing but burn, burn, burn like Roman candles across the night.” – Jack Kerouac, “On the Road”.

***

I went to that fraught instillation of Think About It in support of Tom Powell. Having known Tom since university, it seemed right to show support at the onset of such an important group exhibition. “Mate, this is going to be a big one,” he explained, “and the place is fucking incredible.”

After gunning it over the Malaysian-Thai border in a cramped white van, Tom was accepted, and completed, the RBS-Malihom Aritist in Residence Programme at Malihom Estate in the south of the island back in 2012. The Estate, owned by an old Penang banking family, nuzzles into dense jungle on top of a hill skirting the south's east-west highway. The artists' residences are concrete shells referred to as minimalist, but leave little as to what you might imagine may be living in the Malaysian jungle.

What he produced after six months was a monstrous body of work, forty pieces strong, entitled The Goliard/The Outsider. The Goliard oozed with Byron-esque romanticism over archaic notions of travel and exploration. Maps, moody portraits, passports, stamps, and historic passages written in Edwardian script featured heavily in his first experience of researching a foreign country. The Outsider, however, contained more of a detailed playfulness, taking the mundane of daily life to Malaysians and portraying it in an obscure way through splashes of colour, warped shapes, and elements missing from the painting entirely, adding the excitement of experiencing it for the first time. As a whole, the collection encapsulated his serious interest in the old world – no different to anybody’s idealistic notion of the colonies minus the sawn limbs and pulled teeth – as well as his insatiable desire to experience everything, all the time…now.

At six-foot dead, Tom has an athlete’s build – nurtured by a strict stint at body building in his younger days – neat jet-black hair and a jaw line that makes most women croon. He dresses cleanly and refuses to wear anything but shirts, trousers, and shoes while out at night, suggesting a rational normality – until you get to the eyes. Living in dark purple pools – especially shadowy after a particularly intense night drinking – resides an elaborate character, something intricate and eccentric.

A favourite memory of his childhood involves an Action Man doll, tomato ketchup, fire-crackers from France and/or some wood, a lighter, and gasoline. “I miss being a child sometimes,” he would explain, “and all the times you could re-enact your imagination. Whatever I thought of, I would just make happen in some way. Shit – blowing up and setting fire to Action Men was the best.” In his garden at the back of a semi-detached house in Rotherham, South Yorkshire, Tom would start with syringing tomato sauce in to the head and body of an Action Man. Then, in an execution of small explosions and flaming pyre, the Action Man would be torn apart and reduced to nothing but plastic pulp, spraying fake blood over the grass in an intense desire to perceive reality.

Beyond that, in his twenty-nine years, he has amassed quite a portfolio: artist collectives, numerous exhibitions, online sales, and high-end commissions. “Exposure is a massive thing for an artist. You can be the best painter in the world, but if you leave all your stuff in the bedroom, no one’s going to see it. You’ve got to get out there, meet new people; it’s a business at the end of the day.”

Somewhere between the imaginative – if not eccentric – doll-torturing child and discerning businessman adult is forged a character hell-bent on exacted wanderlust, a controlled, thought-out plan to see – and interpret – as much of the world as possible. “Yeah, I’ve got a goal: I would like to be known; I would like to make money; I’d like to leave a mark. I don’t want to be famous for the sake of being famous; I want to be famous to continue what I want to do on a more epic scale. But, more importantly, I want to enjoy the journey of trying getting to those points. It’s not about those points, they’re a bonus, it’s about going along that road, being able to paint what I want to paint, and being able to explore and discover everything along the way.”

Tom gives the impression as someone well on the way to mastering the rules of life’s great game. In chasing a profession renowned for instability, Tom seems to have concocted his own formula on how do to it sustainably. The term ‘bread and butter’ features heavily in any artist’s daily vocabulary, but Tom – more than most – seems to have a rare, firm grasp on what is expected from an artist to succeed in the world nowadays.

George Town’s emerging contemporary art scene seemed to be the perfect place for artists such as Tom. While contributing to a budding scene, the probability of being noticed by collectors and exhibitors seemed to be relatively high. However, at that time in 2014, nobody knew in what direction George Town would go, and none of the artists had a clear vision of how the city would receive their different artistic styles, much less whether they would be able to build a sustainable life in a country renowned for its crippling censorship laws. Would the state of Penang protect their individual freedom of expression? How would a population – with a growing middle class – largely unused to contemporary art, react to an artistic boom? Would contemporary art benefit a region bursting with heritage or end up swallowing generations of tradition? For better or worse, these questions lived in a shadowy place; not quite in the forefront of the general public's mind but hovering over them like a threatening spectre.

Either way, the hype over art was beginning to take hold in a very real way. What was clear was that for the umpteenth time George Town, and the State of Penang, was being colonised, only this time by a colony of artists.

Chapter 2

“Eiffel saw his Tower in the form of a serious object, rational, useful; men return it to him in the form of a great baroque dream which quite naturally touches on the borders of the irrational ... architecture is always dream and function, expression of a utopia and instrument of a convenience.” ― Roland Barthes, “The Eiffel Tower and Other Mythologies."

“We shape our buildings; thereafter they shape us.” ― Winston Churchill

To call Penang a blank artistic canvas in 2010 would only ring true when considering contemporary art and, even then, there are those that would blush in anger at the statement. The fact is that ‘art,’ in its broadest sense, is as much a part of the state’s history as its melting pot of ethnicities, potpourri of cuisines, historical buildings, and tumultuous political development. Art has been a staple in the everyday life of George Town since its conception as a hub in the Straits of Malacca from as far back as the end of the 18th century. From this time onwards, art has always been and continues to be in Penang, until this very day.

It was during a controversial colonial empire that a swathe of Chinese migrated away from repressive clans and Tamil Indians searching for business opportunities – as well as overseas travel being available to many other Indonesians, Acehnese, Burmese, and Thais – that Penang started filling up under the paternal eye of Captain Francis Light. As an orphaned boy bred for the navy under the tutelage and protection of a wealthy benefactor, Light was the recent buccaneer addition to the proud British Royal Navy and its self-styled amateur business known as the British East India Company. Nestled between an aristocratic, blue-blooded upper crust and a bottom made up of reformed pirates, criminal businessmen, and cad adventures, Light’s addition would raise no eyebrows under the condition that he keep the peace and advance British interest in the region.

In between Light’s open arms grew a segregated society, each community allotted land in what makes the blueprint for present day George Town. Into these allotted spaces grew reproduced cultures of each émigré group. Penang became a colony not only in the sense of being part of colonial Britain, but more a vastly multiplying and quickly developing scene of different monocultures.

Even though not completely harmonious, in the sense that every family has its disputes, this underestimated and largely unheard of patchwork of cultures must have led the way in the world on how different ideologies, religions, and beliefs could live and breathe in the same space without promoting a sense of extreme political correctness and even fear of the ‘other’.

Along Pitt Street (Jalan Masjid Kapitan Keling), one of George Town’s arterial roads, sit four iconoclastic buildings that usually only relate to each other across geo-political boundaries; pit-stops for retirees traveling around the world compensating for a lifetime of corporate grind. From north to south, a distance of less than a kilometre, emerging from Lebuh Farquah, stands the Church of St. George on the right, solemn and lonely in a vast expanse of surrounding land; vast at least when considering it being in the ‘city centre’. Like the Law Courts opposite, and the Town Hall not too far away flanking the padang (village green), the Church of St. George stands in plain white dressed in Georgian architecture; one of the more modest edifices lining Pitt Street, promoting a smart sense of uniform regularity. It is the oldest Anglican Church in Malaysia.

On the same side, a couple of doors down as it were, you pass the squat Goddess of Mercy Temple, usually shrouded in smoke emanating from swollen, pink incense sticks burning along its front. It is a busy place, particularly when Penang erupts with Hokkien festivals, filled with people young and old, rich and poor, male and female, holding small, thin incense sticks between supplicating hands, honouring gods and ancestors as spiritual barter for security, prosperity, and success.

Still heading south, past the The Star newspaper office building and barbers, booksellers, jewellers, and mechanics, the Sri Mahamariamman Temple glides by on your left, just before the deadly and deceptive Pitt Street/Lebuh Chulia traffic lights. Traversing the tarmac road in front of silver gilded doors is a stretch of terracotta coloured tiles, like an honorary red carpet, breaking the monotonous black asphalt in two. Flanking the doors stand thin, Georgian-esque pillars supporting a flat entrance way. Decorating a pyramidal tower, smaller than the main tower looming large behind it but of same design, are brightly coloured figurines representing Hindu deities and saints, some of which are recognisable – the elephant head and human body of Ganesh is an obvious point of reference even though he looks boyish and his head is painted salmon colour, not blue; some of which are not – wild looking men with bulging eyes, forked beards, and mouths wide open displaying sharp elongated tongues, crouched, with hands held up in a position that would make the Maoris themselves question the very origins of the Haka. Its immaculate condition barely gives the impression of it being the oldest Hindu temple in Malaysia.

Traversing those perilous traffic lights, the Kapitan Keling Mosque comes into view large and impressive almost immediately on the right. Situated in pristine grounds with seemingly white-washed walls transforming into yellowed ochre under a setting sun, the mosque shines on those balmy Penang evenings as a beacon, announcing the historically Muslim-Indian community surrounding it. Despite its reverent ambiance, and serious connotation, ‘Keling’ implies an absence of political correctness yet to hit the island’s shores; ‘Keling’ being a derogatory word for the community the mosque is meant to represent.

However, the greatest significance of George Town’s churches, mosques, temples, and Strait-settlement shop houses is the catalytic stimulus they provided for art. They represent art’s close cousin – ‘craft’ – and the skill and effort required to create them. Such specific knowledge and unwavering tradition goes some way towards suggesting that George Town has always been a natural petri dish in which art could flourish based on the constant artistic inspiration these buildings – in such close proximity – afforded artists, whether local or foreign. And, it is a tale of inspiration that stretches back as Penang’s first inception as a colony.

From as far back as the 16th century, cartographical evidence of European exploration in South-East Asia was created in the forms of highly detailed, multi-coloured maps. At the end of the 18th century, Laurie and Whittle commissioned Chart of the South Channel from Prince of Wales Island [Penang Island] to Sea, a map based on survey work conducted by Captain H. R. Popham, detailing the eastern half of Penang Island and the Strait of Malacca separating it from the mainland. It came complete with channel depths, mudbanks, rocky outcrops, rivers, plantations, and even a detailed layout of Fort Cornwallis together with a street plan of George Town. It may not be considered art per se, but nowadays maps of this nature adorn rooms the world over and, as we are about to see, art in Penang throughout its history has taken on a broad meaning.

Art of a more traditional nature – in the form of painting – first began to surface in Penang under British colonial development. At the beginning of the 19th century, Captain Robert Smith started a collection of realist paintings depicting Penang Island at the time. Among those documenting the Island’s natural beauty (The Cascade, 1818), and what it suffered in the face of development (Forest Clearence, 1818), were romantic vistas punctuated by the stamp of imperial expansion. In The Mill, 1818, one would be forgiven for thinking that the copse of trees and small lake surrounding a decidedly English-looking cottage was taken from the English countryside, if it weren’t for the lone, thin palm tree dominating the right of the painting. A couple entitled Signal Hill, 1818 [now known as Penang Hill], portrayed the view of and from the hill, not without the unmistakable white dot of a colonial bungalow. Again, in Glugor House, 1818, Smith captured a swathe of plantation land on the Island, the centre of the painting dedicated to a plantation bungalow. Possibly in his most famous rendering, Suffolk House,1818 – Francis Light’s home – Suffolk House proudly sits centre stage in grand Georgian opulence atop manicured grounds sloping down to a river.

Other art forms of the time were just as reflective of the cultures from which they came. Most notably, Chinese immigrants who had, by the mid-19th century, acquired some wealth and stability, invited artisans from China to build houses, temples, and clan houses in the traditional Chinese style. In those days – unless you were part of the British contingent – people had little time for romantic notions of artistic beauty and its potential for uniting the world. The early Chinese immigrants to Penang were more focused on laying rights to land as a base for which they would call their new home. With the prospect of either establishing outright an overseas Chinese community, or returning to China’s war-torn provinces, these buildings established their right to live in Penang as well as their potential to grow – clan-houses and temples offering immediate support to new Chinese immigrants. As such, these buildings – the Khoo Kongsi, Yeap Kongsi and Goddess of Mercy Temple, among other examples dotted around George Town and the Island – were statements of ownership of community areas, like hoisting a flag. They were proclamations that their communities intended to settle in George Town for good, and that they were part-and-parcel of the regions development.

Others among that growing artistic network were commercial artists, sculptures, portrait painters, photographers, and calligraphers, all providing services to aid art within Chinese communities. According to a historical report by Dato Koh Wee Khian:

“The sculptures, architectural forms and paintings in Kek Lok Si Temple and Khoo Kongsi reflect the skill and ability of the Chinese artisans and sculptors, and the taste at that time [mid-19th century] of development of art… Most of the calligraphers were clerks working in the commercial firms during the day and set up stores along the roadside in the evening to provide services to the Chinese community. During festival season on Chinese New Year, their calligraphy was hung at doorways or on the walls of the common guests' area. Display of works of calligraphy and demonstration at public areas were common cultural activities regarded as an early form of exhibition in the early days.”

At the beginning of the 20th century, rather than ‘art’ being used as a confirmation of cultural identity within the Chinese communities, it took on more of an identity centred on art itself. With the arrival of Yong Men Sun in the 1920s, a group of local Chinese artists and art lovers established Penang’s first art society, the Ying Ying Art Society, of which Yong Men Sun – well regarded for his watercolour representations of rural life on Penang Island – was a committee member. The society’s opening in 1936 is considered the first grand scale exhibition held in George Town, an occasion officiated by His Excellency Huang Yan Kai, the Ambassador for China in Penang. The high quality of the exhibits, which included works of sculpture, water colour, oil, Chinese art, calligraphy, photography, and stamps by local artists, attracted many supporters. Most notably, it caught the eye of the renowned Chinese Xu Bei Hong, who then spent months in Penang holding exhibitions to raise money for the war in China. His arrival, even though cut short, was to pave the way for Penang’s current art society.

From 1942 to 1945, all art production stopped as a result of the Japanese occupation. In the style of war at that time, a large part of the Japanese army’s arsenal in conquering a people was propaganda. As such, art in Penang was seen to be contrary to the Japanese mind-set and the values they tried to instill, and was, therefore, banned in an effort of censorship that rivaled the Nazi’s propaganda in Germany.

Either way, after the Japanese occupation, and a rallying call from Xu Bei Hong to the Penang Chinese art and cultural community, the Penang Art Society was established in 1953. With Loh Cheng Chuan – an old friend of Xu Bei Hong – elected as its Founding President, this conglomeration of poets, artists and cultural advocates would set the precedent for the oldest art society in Malaysia, which still holds sway to this day with over 300 members.

Chapter 3

“Collective will supplants individual whim.” – Samuel P. Huntington

"A good piece of art work will be at a disadvantage if it is not properly promoted. This is why mediums such as the Penang Art Society played a crucial role as it has unceasingly facilitated and tirelessly promoted Malaysian art works." – Dr Mohd Najib Ahmad Dawa, Director General Malaysia National Art Gallery.

"He who controls the past, controls the future; he who controls the present, controls the past." – George Orwell, “1984”.

"Man is conceived in sin and born in corruption, and he passeth from the stink of the didie to the stench of the shroud." – Willie Stark in “All the Kings Men,” Robert Penn Warren, 1946.

The Penang Art Society serves as a prevalent example of the personification of art from culturally iconoclastic buildings. It – and other groups like it – shifted the notion of art from early edifices designed as cultural declarations to human collectives charged with nurturing the existence of art into a professional discipline, with continually growing importance and dedicated to ever greater exposure for artists.

In its own words, the Penang Art Society aims to: “[act] as a platform for artists to display their creativity and to promote local art in Malaysia. Taking advantage of the Asian art boom, the society is aiming to not only promote art locally but also to unite all Malaysian artists and to expose Malaysian art to the world.” In general, it is a mission statement largely regurgitated around the world by other art societies, collectives, and forums. But, there are two points to take from it that clarify the state of George Town’s and Penang’s art in 2010.

The ‘Asian art boom’ they refer to had not hit Penang’s murky shores by that time, but this is not to say that it was non-existent in the region. Art from the East and South-East Asia had gained steady attention around the world for the past thirty years and was providing a healthy income with glittering possibilities for those who were picked up by the bandwagon. Artists from Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam, and China were becoming more well-known in the world through being collected in Western art markets, and the value of their art was rising because of it.

Among those included were Malaysian artists who are referred to as “titans” of the Malaysian art scene today. In Kuala Lumpur, the art auctioneers Henry Butcher held their inaugural auction in October 2010 entitled ‘Malaysian Modern and Contemporary Art Collection’ and highlighted the value of some of Malaysia’s artistic upper-crust. Datuk Ibrahim Hussein, considered one of Malaysia’s most iconic artists, sold The Dream (1989) for RM500,000; a surrealist piece depicting a naked woman – in the centre, and incorporated with collage strips – falling through a background of luminous strokes of blues, reds and purples. Other artists – Lim Kim Hai and Dato’ Mohd. Hoessein Enas – also sold for six figures with Gentle Breeze (1983) and Javanese Girl (1954) respectively. Another Malaysian great – Latiff Mohidin – had a piece of work entered into the auction, Gelongbang Bumi [Movements of the Earth] (1989), with an owner’s reserve of RM600,000, but it did not sell.

In addition, early members of the Penang Art Society were represented in the 2010 Henry Butcher auction. Of worthy note, Dato’ Chuah Thean Teng sold his piece, Mother with Children (circa. 1986), over the estimate for RM114,400; a Batik piece of maternal affection depicting a mother breastfeeding her infant child while her other child looks on. He moved to Penang when he was 14 years old and, even after continuing with art through the Japanese occupation by making political woodcuts under the pseudonym Choo Ting, Dato’ Chuah joined the Penang Art Society almost immediately after its conception. In 1967, his most famous painting, Two of a Kind (1965) was accepted by the United Nations as the design for the UNICEF Christmas card, the first time a Malaysian artwork was accepted by the world body. In 1987, his painting Tell you a Secret was selected again by UNICEF. He died in 2008 as the world acknowledged founder of Batik painting.

There were six other early members of the Penang Art Society sold at the auction, all ranging from RM6,000 to RM35,000. In comparison to the rest of the world, however, these sales were dwarfed by artworks sold in the West. In March 2010, Jasper Johns sold Flag (1954) for $110,000,000 in a private sale – a representation of the American flag in encaustic, oil paint and news print collage with 48 stars and 13 alternate red and white stripes including elements of pop-art, minimal, art and conceptual art. It is the American flag – which on the face of it was imbued with Johns’ sense of patriotism having been named after the solider who saved the fallen flag at Fort Maultrie in the American Revolutionary War – William Jasper – mixed with an obvious reflection of U.S. flag-orientated history at the time. But what made Steven A. Cohen – hedge fund manager and founder of Point72 Asset Management and S.A.C. Capital Advisors, as well as a notable art collector – buy it at such a high price was the ambivalence expressed below the surface over America’s troubled existence at the time (Senator Joseph McCarthy was embroiled in a series of hearings against the U.S. Army that had the two sides accusing each other of bias and Communist-elements respectively), as well as remaining an iconic representation of Neo-Dadaism. Its most valuable factor lay in the confusion of art critics to confidentially describe it as a flag or a painting of a flag – to which he answered it was both, a riddle as perplexing as the Gordian Knot. The U.S. flag would go on to inspire forty other of his paintings.

In that same year, Pablo Picasso’s Nude, Green Leaves and Bust (1932) sold at Christie’s in New York for $106,500,000, the highest any artwork had been sold at auction until it was beaten by Edvard Munch’s The Scream (1895) for $119,900,000 at Sotheby’s in New York. Picasso’s portrait of his then mistress and muse Marie-Thérèse Walter is a five-foot tall impressionist piece, its natural beauty stemming from vibrant blue and lilac tones. Such beauty, innocence, and love stood in stark contrast to a European political environment bristling with the onset of war at the time of its completion.

The contrast in value between the examples of Johns and Picasso in the West and Malaysian artists in the East is mind-altering. Or, maybe not – but it certainly quantifies what level of ‘art boom’ the Penang Art Society were trying to capitalise on as described in their mission statement. While seemingly unfair to compare Malaysian artwork and its value to some of the most famous painters to have ever lived, the comparison does question as to why Johns’ concern over government in-fighting in 1954, for example, rings louder and longer than the Malayan Emergency – in full swing during 1954 – or the bombs and arson of the Sabah Riots in 1986; events experienced, or at least lived through, by Dato’ Enas and Dato’ Chuah respectively in the years their 2010 Henry Butcher sales were created.

In part, the answer lies in the rape and stunting existence of colonial empires in Malaysia for as long as 200 years until August 1957, when the country won its independence from the British. In fact, it wasn't until August 1965 that Malaysia would enjoy a period of true sovereignty uninhibited by border disputes after Singapore was expelled from the Federation of Malaysia, creating what we now know as Malaysia today. In this respect, Malaysia as a democracy is a young nation indeed, barely into its adolescence; at fifty-one years old in 2016, it is younger than most of my parents’ generation. By the time Johns finished Flag, American society was asking hard questions over a capitalist government and career politicians. The Beatnik generation was soon to morph into a generation of disenfranchised youths that would protest en masse against increasingly corrupt and bloodthirsty political agendas, while Malaysian’s did not even have a country to call their own.

True to the old adage that history is written by the victors, Western media corporations inevitably shunted Malaysia into insignificance. As for Malaysia’s artists, this created a mountain that represented a long, hard, Sisyphean struggle to conquer, which left their works dealing in pennies and cents compared to their Western counterparts. In this context, it is no wonder that even collectives such as the Penang Art Society, with strong memberships, had tried and arguably failed to expose the works of Malaysian artists to the world. Without its own international publicity over – say – a political scandal, Malaysia just did not register on the international media’s radar – or at least not in any way that mattered.

So, the prospect of exposure has always been an uphill battle for Malaysian art societies and collectives, whether promoting artists on a national or international level. To make matters worse, the widely acknowledged yet rarely reported censorship laws in Malaysia in 2010 continued to act as a main crippling agent to Malaysia’s art scene. What would serve as a prime example of Malaysian censorship laws blocking art’s progress – particularly art with political connotations – were a collection of works by the cartoonist Zunar. Compiled between 2005 and 2009, his three works “1Funny Malaysia”, “Perak Darul Kartun [Perak Land of the Cartoon]” and “Ius Dalam Kartun [Issues in Cartoon]” were banned on 24th June 2010 by the Home Affairs Ministry. In Zunar’s own words taken from a statement he made a month later on Reporters Sanz Frontiers (RSF), he described the banning as being “politically motivated and designed to block alternative views and critical voices… a mockery of press freedom and freedom of expression.” It is one example of censorship based on an irrational governmental fear over an unseen menace bent on subverting the national peace… or more accurately, threatening political control.

Zunar’s banned pieces read like a Stieg Larsson crime novel of unbelievable crimes nestled at the very top of government. The content satirised government misconduct and corruption ranging from the multi-million dollar Scorpene bribing scandal, the resultant murder of translator Shaariibuugiin Altantuyaa by C-4 explosive, political conspiracy against opposition leader Anwar Ibrahim, misuse of public funds, and suppressing the media through the use of draconian laws entwined in the Internal Security Act, the Printing and Publication Act, and the Official Secrets Act. As content goes, it is a litany of grave concern for any public official that may wonder how it became the inspiration behind a cartoonists work in the first place. No wonder then that the Home Affairs Ministry Secretary-General Mahmood Adam explained: “All three publications have been banned for its contents that can influence the people to revolt against the leaders and government policies. The contents are not suitable and detrimental to public order.” Any tax-paying Malaysian will tell you it is not the satirical interpretation of these events that incites revolt, but the events themselves, which are such public knowledge that they remain a sore in the government’s side until today.

Perhaps the most important point to take from this for now is Zunar’s personal interpretation of what such a ban entails for the freedom of a people. When speaking about the ordeal, Zunar encapsulated perfectly the power of art when he said: “My banned cartoons highlight these subjects and my intention is to give the correct perspective and information to the reader. It is a duty for any political cartoonist to be a ‘watch-dog’ over the authorities and to represent the voice of the people through art.”

The type of malignant fear such censorship produces among those in any art scene is obvious. It is a fear that those brave enough to walk the art-censorship-tightrope consider with every new exhibition or concept in Malaysia. Valentine Willie, a notable Malaysian artist, collector, curator, gallerist, and art impresario was forced to remove a multimedia piece by artist Fahmi Reza from his gallery Vallentine Willie Fine Art that satirised the then new Prime Minister Najib Razak. Without a directive from the Home Affairs Ministry, Valentine’s decision was purely one of self-censorship. Yet, coming from one of the most recognisable personalities on South-East Asia’s art circuit, having worked in the sphere of art for over 40 years in Malaysia and the continent, it also imparts a wise lesson in self-preservation.

Being forcibly steered away from producing, exhibiting, or selling art without any political motivation or intent, incapable of being created without complete freedom of expression, would point to an environment unfit for any form of art boom. On the face of it, Malaysia seemed the least likely country in South-East Asia to undergo an artistic resurgence. But, lying dormant in Penang – a northern state defended by an opposition party from the talons of the federal government in Kuala Lumpur – was an atmosphere with the catalytic potential to spread art among a population that had been playing catch-up with the rest of the world for years.

Dear All,

Well, it has finally been confirmed; "Malaysia's Canvas" will be published early next year!

I have signed with the Malaysian publisher Gerakbudaya ( …

Dear All,

Thanks to all of your outstanding support I have finally reached 250 pre-orders. Malaysia's Canvas has now been queried to 25 independent publishers …

Dear All,

I have been afforded an extension to my campaign for Malaysia's Canvas of an extra 20 days. The reasons for this run deep …

Dear all,

I recently released a newsletter detailing the campaign for Malaysia's Canvas. If you could share this with your family, friends and colleagues it …

Dear All,

Find the link to my first author interview discussing my motivations for writing Malaysia's Canvas. This has been published online by a funky …

Hi All,

Just a quick update to point you all to an article I wrote in 2015 on the state of George Town, then. It …

Dear All,

Pre-orders have continued to rise steadily, albeit not on the same trajectory as the initial surge. However, I am pleased to say that …

Dear All,

After reaching that golden 100 pre-order mark, I have been approached by an independent publisher already, slightly ahead of when I thought they …

Dear All,

Thanks to your overwhelming support, I have reached 100 pre-orders in the first 10 days!

The new target is 250 by 8th May, …

Dear all,

Find the link below to Malaysia's Canvas new campaign video. After that rather embarrassing first attempt, this now provides a snippet of the …

Dear All,

I am proud, and grateful, to announce that Malaysia's Canvas has reached the number 1 spot in Journalism on Publishizer!

As well as …

Dear Pre-Orderers!

I have reached 58 pre-orders, which puts me half way to my next push onto Publishers!

And it is down to all of your …

Great work James, excited to the book!

What a great project!

Ha that picture!

Good man on getting cracking with the book, and now you have to acknowledge me muhuhahaha!

PS. Should be seeing your face in August.

kathywood88@gmail.com

😁

James, we had no idea what you were up to! We look forward to the finished article.

Cheers,

Alison and Chris

Best of luck with this Spring! You can drop the copy off next time I see you in the UK!

Best of luck with your new adventure James! I can't wait to read your book.

Greeting from Belgium...

Great job, James, Best wishes on getting it published!

Good luck with the book Spring! Great to see it's done and out there.

Wishing you luck dear James and at least reaching the 100 book mark, and look forward to reading your opus. You'll get there, I am sure !

Can't wait to read it. Good luck with your campaign.

Congrats James! Amazing accomplishment. Wishing you the best!

Deirdre

Well done James. Looking forward to seeing your book

Looking forward to reading the book! Penang art scene has always fascinated me

Kristijonas Kabasinskas

Looking forward to reading it!

All the best Dr James 😊

Cu. Bernd

Good luck James! Terry.C.Parmely@gmail.com

ivplee@gmail.com

All the best, James!

So very proud of you James. X

James

Best of luck with the Book

Love Rich and Penny

Hi Jame, looking forward to your publication. See you in a couple of weeks. Mike

Congrats James! Good luck on your new book. Looking forward to receiving our copy :)

Done!!Teacher Springer ;)!!

Nice work mate!

Well done mate. Good job!

Best of luck for your book, James !

Well done !!

The $30 one is for me !! The $20 one is for Luke !! He asked me to get it for him xx Two different autographs please!!xxx

Hey James, I ordered the book! It looks great! Sorry, I meant to do it before, thanks for reminding me! :)

Great job James! I wish you good luck for this new adventure. kisses JP

I can't wait to read it! I hope it brings you what you hope for. Best wishes.

Jimmy Springer! Good luck mate, can't wait to get my hands on my copy. Only you could use the words 'exotic quicksand' to describe somewhere - absolute word porn!

All the best of luck in your book James & looking forward to it

Congrats James

Good Man James. The book has been preordered for Penny and I. Best of luck reaching your publishing goals.

Looking forward to this book James! As an author who's first book was released initially in Malaysia, I've spent a lot of time there and look forward to taking a trip down memory lane with your book

I love you, brother!

Looking forward to reading it...

Well done for reaching 250 orders, James !

Look forward to reading all about the art scene in your wonderful city and seeing you this summer. Warm regards

Blake and Boky

Congratulations Sir!!

$20 Sold out

30 readers

LIMITED

• Early Bird 'Signed' Copy

• Free Ebook (PDF, ePUB, MOBI)

• Free shipping

Includes:

$25

15 readers

• 1 'Signed' Copy

• Free Ebook (PDF, ePUB, MOBI)

• Your name Acknowledged in the book

• A set of 12 Zodiac postcards by Tom Powell

Includes:

$25

15 readers

• Early Bird 'Signed' Copy

• Free Ebook (PDF, ePUB, MOBI)

• Your name Acknowledged in the book

• Free shipping

Includes:

$30

9 readers

• 1 'Signed' Copy

• Free Ebook (PDF, ePUB, MOBI)

• Your name Acknowledged in the book

• 1 art print by a selected artist featured in the book

Includes:

$40

2 readers

• 1 'Signed' Copy

• Free Ebook (PDF, ePUB, MOBI)

• Your name Acknowledged in the book

• 1 photo print by Howard Tan, Penang's famous street photographer.

Includes:

$50

9 readers

• 2 'Signed' Copies

• Free Ebook (PDF, ePUB, MOBI)

• Your name Acknowledged in the book

• Set of 12 Zodiac postcards by British-born artist Tom Powell

• Free shipping

Includes:

$100

11 readers

• 5 'Signed' Copies

• Free Ebook (PDF, ePUB, MOBI)

• Your name Acknowledged in the book

• 1 art print by a selected artist featured in the book

Includes:

$500

1 reader

• 20 'Signed' Copies

• Free Ebook (PDF, ePUB, MOBI)

• Your name Acknowledged in the book

• 1 photo print of George Town's city streets and a series of 5 note cards by Howard Tan, Penang's famous local photographer.

Includes:

$1000

1 reader

DISCOUNT:

• 100 Copies of Malaysia's Canvas by James Springer at $10 ea.

Includes:

on April 10, 2017, 1:01 p.m.

Well done James - looking forward to reading the book!