Innovation and Entrepreneurship in the Socialist Republic

Challenges, efforts, and successes of Vietnam’s youth, local startups, and foreign entrepreneurs during a time of transition between tradition and modernity.

Ended

Order on Amazon:

1) https://www.amazon.com/author/andrewprowan

or on my website:

Publish Date: April 2, 2019

_____________________________

Today, talk of “VCs” in the Socialist Republic of Vietnam almost always refers to the growing ranks of Venture Capitalists instead of the Viet Cong—a name that many people associate with the Vietnam War. With a population of 95 million people, Vietnam has more than 1,500 active startups, making it the third largest entrepreneurial ecosystem in Southeast Asia (behind Singapore, the major financial hub in the region, and Indonesia with 260 million people, respectively). The median age in Vietnam is 31—and there over a million babies born across the country each year, even with a two-child policy recently loosened. Furthermore, OECD (2012) PISA (Programme for International Student Assessment) results reveal that Vietnam’s 15-year-olds perform on a par with those in Austria and Germany. Remarkably, about a quarter of Vietnam’s population is 14 or younger, with almost 70% of the population between the ages of 15 and 64.

In 2015, there was a 139% increase in venture capital investment in Vietnam resulting in 67 deals—up from 28 deals in 2014. Moreover, the number of deals have increased, on average, from 20 deals per year in the period from 2011-2013 to 48 deals per year in the period from 2014-2016, based on data aggregated by Topica Founder Institute. Of note for 2016, seed and Series A deals made up 70% of the 50 documented deals, according to Topica Founder Institute. Additionally, the number of large deals (greater than $5 million) remained relatively unchanged (10 in 2015 and 11 in 2016), but their collective value grew 60% ($63 million compared to $100 million). However, with three major startup hubs across the country (Hanoi, Ho Chi Minh City, and Da Nang), Vietnam lacks the transparency, clarity, and context for anyone interested in startups—especially incoming waves of entrepreneurs and investors from overseas.

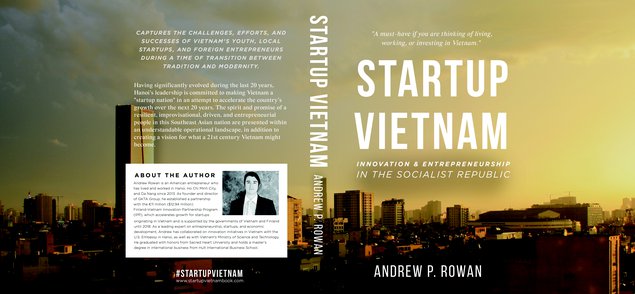

Startup Vietnam: Innovation and Entrepreneurship in the Socialist Republic captures the challenges, efforts, and successes of Vietnam’s youth, local startups, and foreign entrepreneurs during a time of transition between tradition and modernity. Having significantly evolved during the last 20 years, Hanoi's leadership is committed to making Vietnam a “startup nation” in an attempt to accelerate the country’s growth over the next 20 years. The spirit and promise of a resilient, improvisational, driven, and entrepreneurial people in this Southeast Asian nation are presented within an understandable operational landscape, in addition to creating a vision for what a 21st century Vietnam might become.

For the past four years, I have been working in Vietnam programs and/or activities supported by the governments of Vietnam, the United States, and Finland as well as private sector advocates (local and international investors, entrepreneurs, and developers) to further the development of the enterprise ecosystem. Furthermore, as a qualified participant-observer, I am an entrepreneur, consultant, advisor to startups, and writer who has contributed to Tech In Asia, e27, and Tech Wire Asia—the leading news portals for startups in Southeast Asia.

As the interest in Vietnam continues to increase from abroad, more foreign entrepreneurs and investors are flocking to Vietnam where they will experience culture shock. I, too, experienced the “Vietnamese way of doing things,” and it can be quite frustrating from a Western perspective. My role in Vietnam’s enterprise ecosystem has been as super-connector—optimizing relationships inside and outside Vietnam. I am able to engage in these activities because of my experience in Vietnam—ranging across multiple industries, from IT and media to startups.

There are only a handful of writers who cover Vietnam’s enterprise ecosystem; I began writing in 2014 because I saw a gap in coverage on the exciting and interesting things happening in Vietnam. However, most coverage of Vietnam’s recent entrepreneurial trajectory lacks context (from foreigners), or very closely resembles a press release (from locals). And it is very early in Vietnam’s trajectory so there are some bad actors and instances where the “blind are leading the blind”—for the loudest players are not always the best or the ones with the most experience (foreigners included).

So I wish to present a solid view of where Vietnam is heading, offering a range of perspectives of the entrepreneurs, investors, and other allies in whom I trust or have confidence. At the same time, I seek to capture the incredible spirit of the people who are building a better future in Vietnam. Often, there are contradictory positions, statements, edicts, and decrees regarding policies relevant to entrepreneurship in Vietnam. Still, local and foreign entrepreneurs have found a way to persevere. How is it possible?

Startup Vietnam aims to answer that question and other questions which incoming foreigners (and already resident foreigners) might have about Vietnam’s already "enterprising" ecosystem.

To me, Vietnam is the best-kept secret in Southeast Asia. People hear the word, “communist” and they "switch off." However, for those "in the know," there are plenty of opportunities but they must overcome cultural challenges and approach the situation with the appropriate expectations. Furthermore, there are four million overseas Vietnamese—some of whom may want to return to their homeland, but are not sure how they will be received. Some other basic questions include:

• Do I call Ho Chi Minh City by its official name, or should I refer to the city as Saigon?

• My parents fought for the South (Republic of Vietnam)—will I have any trouble?

• How can I help Vietnam?

• What is life like for Viet-Kieu (Vietnamese born overseas) in Vietnam?

• Will Hanoians hate me?

Thus, Vietnamese-Americans and other members of the diaspora will be interviewed to share their perspectives in specific chapters. Locals in Ho Chi Minh City, Da Nang, and Hanoi also will be interviewed, as well as foreigners across these three cities so that a holistic view is presented on operating in Vietnam for those who are interested.

The major markets are 1) Viet Kieu (or Overseas Vietnamese); 2) foreigners who will do business in Vietnam; 3) foreigners who will tour Vietnam; and 4) foreigners who are researching Vietnam but who will not or have not come to Vietnam.

The chapters are divided in a logical fashion to allow the reader to digest one portion before continuing on to the next topic. First, “Why Vietnam?” is established so that the reader understands what is at stake. The shift from communism to capitalism is a once-in-a-lifetime event—and it’s happening now. However, one can live in Vietnam without experiencing it, so the next chapter covers "Vietnam Up Close.”

Chapter 5 addresses the “New Vietnam Mindset,” which is led by entrepreneurs, thought leaders, and members of civil society in the country. The next chapter focuses on how startups can achieve growth in Vietnam followed by the beginnings of a startup nation. Chapter 8 explores challenges and opportunities in Vietnam, before outlining the requirements for success in the following chapter. Chapter 10 sets forth a vision for Vietnam in the future before the last chapter, which gives actionable steps for foreigners to get involved in Vietnam.

In this proposal, Chapter 3 (Vietnam Up Close) is included. In short, I am well-positioned to write about entrepreneurship, startups, and innovation in this important Southeast Asian nation—which will only grow in importance.

Above: Hardcover design; cover photo: Andrew Rowan

Section I: More Than Meets the Eye

Chapter 1: Why Vietnam?

Chapter 2: Vietnam from Afar

Chapter 3: Vietnam Up Close

Chapter 4: Beneath the Surface

Section II: The New VCs of Vietnam

Chapter 5: A Mindset Shift

Chapter 6: Catalyzing Growth in Vietnam

Chapter 7: The Beginnings of a Startup Nation

Chapter 8: Challenges and Opportunities in Today’s Vietnam

Section III: Requirements for Success

Chapter 9: Building a Solid Foundation

Chapter 10: Localizing Global Solutions

Chapter 11: Being a Part of Vietnam’s Success

---

Chapter 1: Why Vietnam?

Vietnam has created and experienced a remarkable growth and development story in the last 30 years—second only to China. Since 1986 and the beginning of the Communist Party’s Doi Moi (“renovation”) policy, Vietnam has steadily integrated its economy into the global marketplace, including the country’s accession into the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2007. By 2010, poverty in Vietnam had been reduced to around 20% from 60% in the early 1990s.

Vietnam doesn’t have a market of over a billion people like China or India. Yet, with a population of over 90 million people, it has more than 1,500 active startups, making Vietnam the third largest entrepreneurial ecosystem in Southeast Asia (behind Singapore, the major financial hub in the region, and Indonesia with 240+ million people, respectively). The World Bank and the IMF have both recognized Vietnam’s development success. In 2013, the World Bank acknowledged Vietnam’s path from one of the world’s poorest countries to a lower middle-income country in the span of 25 years. Last year, Christine Lagarde, Managing Director of IMF, delivered remarks in Hanoi about Vietnam “gearing up for the next transformation.” If Vietnam is able to avoid the middle-income trap, it can then provide a blueprint for similar countries. Furthermore, as a country among the first to be impacted by climate change, Vietnam will serve as a litmus test for how a rising sea level will impact countries around the world.

On a macro level, annual trade is projected to increase by more than $200 billion by 2020—this presents a huge opportunity to develop trade-oriented services based on Free Trade Agreements (FTAs). The middle and affluent class is expected to increase to 33 million Vietnamese by 2020, more than double the number from 2012 (14 million) according to BCG. And according to a recent Knight Frank report, by 2025, Vietnam will see the largest creation of ultra-high net worth ($30+ million) individuals in the world. With increased purchasing power, these consumers will desire new products and services as their values of self-expression are reinforced.

Further questions:

• Why does Vietnam matter?

• Why is there a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity in Vietnam?

• How might climate change alter Vietnam’s course?

• How can Vietnam be an example for other countries?

• What is Vietnam’s current trajectory?

Chapter 2: Vietnam from Afar

Many people outside of Vietnam first and foremost think of the wars fought there. But that’s not the everyday Vietnam that is undergoing massive change. The urban changes in Vietnam that are visible on the surface level and they are raw, real, and deep-rooted. (In fact, it would be hard not to notice the hustle and bustle as well as omnipresent noise pollution in the most populous cities.) It can be confusing for foreigners to reconcile what they read or hear with what they see once landing in Vietnam: it’s changing literally right before your eyes in the major cities. Vietnam is more than just a collection of rice paddies, conical hats, and water buffalo—and life here has progressed beyond scenes from Full Metal Jacket and Apocalypse Now. How is Vietnam different from the one you might have seen in the headlines (if at all)?

Further questions:

• How does the real Vietnam differ from Vietnam from Afar?

• What hasn’t changed from this outside perception?

• What has changed, even within a few years?

• How much of what you read and hear is true?

• Once inside, how much of what you see is real?

Chapter 3: Vietnam Up Close

When arriving in Vietnam, expats naturally gravitate to Ho Chi Minh City (the economic center) or Hanoi (the capital). District 1 of Ho Chi Minh City is but one version of Vietnam—but it is usually where expats congregate, with the exceptions of District 2 or District 7. Furthermore, there is life outside of Hanoi’s Tay Ho district, the preferred enclave for expats. Is it possible to live in Vietnam without experiencing Vietnam? How can you reduce miscommunication (across cultures) and set the right kind of expectations (for everyone to work towards success)?

Understanding how to operate here (professionally or doing business) is completely different from the structured and formal environment in the West. In one important matter, contracts don’t mean anything—relationships do. When does "Yes" really mean "Yes?" Nuance and context are the key to figuring out many things here for business. And then there are the everyday challenges of living in Vietnam. How can foreigners connect with Vietnam on a deeper level?

Further questions:

• How to avoid common pitfalls?

• What should you expect?

• What to make of conflicting information?

• What questions should you ask?

Chapter 4: Beneath the Surface

Vietnam’s former tourist tagline used to be “The hidden charm.” Insofar as this relates to the inner workings of the country’s politics and economy, much of what happens in Vietnam occurs beneath the surface. The commonly-read headlines about Vietnam (40 years after the war, U.S. presidents making friends with former enemies, and Ho Chi Minh City versus Hanoi) aren’t really accurate—and what I’ve written in my earlier articles about startups, technology, and innovation in Vietnam isn’t the entire story. Vietnam is known for its political stability, but that’s true only up to a certain point. We explore the informal economy, as well as some of the more informal aspects of life in Vietnam.

Further questions:

• What don’t we usually talk about or mention when it comes to Vietnam?

• Is there a “dark side” to operating in Vietnam?

• How does one really know what’s going on?

• What to look out for when doing business or living in Vietnam?

Chapter 5: A Mindset Shift

There is an array of modern entrepreneurs who are trying to scale companies within and outside of Vietnam. Their stories are shared in this chapter.

Further questions:

• How is this new mentality taking shape?

• Is this the exception or the formation of a new rule?

• What’s the path of success?

• Is all the “bad press” (lack of transparency, crony capitalism, restrictive internet regulations, etc.) true?

• What about the “good press” (Asia’s next dragon or tiger, a rising middle class, and an IT outsourcing haven, etc.) being true?

• Is everyone just trying to make a "quick buck" in Vietnam?

• Are foreigners all walking ATMs? (Yes and no.)

Chapter 6: Catalyzing Growth in Vietnam

Vietnam is at such an early stage of its development—the country has only been truly “open for business” since 1995 as a result of the post-war embargo. The level of depth and sophistication in the country just isn’t there—from workers to mentors to local investors and other nouveau riche players—everyone seems to be learning as they go. The entrance bar is low. But is that a good thing? Will entrepreneurs and other nascent actors do more harm than good? We sit down with the most active investors in Vietnam.

Further questions:

• What do Vietnamese entrepreneurs need to work on?

• What do angel investors in Vietnam need help with?

• Should entrepreneurs tackle the national market or aim for a regional play from day one?

• What are the most effective ways to grow in Vietnam?

Chapter 7: The Beginnings of a Startup Nation

The pieces in Vietnam are beginning to assemble: events, government support, and an active interest in entrepreneurship from varying segments of the population. Coworking spaces are springing up as the basis for communities to form, but what’s next?

Further questions:

• What do people on-the-ground in Vietnam see as the humble beginnings of a startup nation?

• What’s the rate-limiting step in the process?

• What are the building blocks being put in place today?

• How can foreigners help?

Chapter 8: Challenges and Opportunities in Today’s Vietnam

Since normalizing relations with the U.S. in 1995, Vietnam has grown at a neck-breaking speed over the last twenty years. The next twenty years will test all levels of Vietnam’s society as development continues to quicken its pace and new technologies and ways of communicating are introduced to Vietnam.

Further Questions:

• What is the vision that the Vietnamese and others share for this country of soon-to-be 100 million people?

• Wherein do the opportunities lie? Mentor networks? Angel Investor networks?

• What about the changing role of women in Vietnam?

• Will the country realize economic/social equality in some form?

Chapter 9: Building a Solid Foundation

Last year, the World Bank and Vietnam’s Ministry of Planning and Investment (MPI) released a report about what Vietnam might look like in the year 2035. Publicly, Hanoi’s leadership embraces innovative practices, but when it comes to implementation there seems to be a disconnect in some areas. It has outlined a long-term vision for Vietnam but how exactly will the nation get from "here" to "there?"

Further questions:

• What about the necessary investments in education, training, technology?

• What is the government of Vietnam doing?

• What about foreign allies/competitors?

• What kind of commitments are we talking about?

• Could a free and open and more democratic society be on the horizon?

Chapter 10: Localizing Global Solutions

A vibrant private sector will play a pivotal role in reaching “Vietnam 2035.” Throughout the country, 70% of Vietnam’s more than 90 million people live outside of urban areas. So what might work in one part of Vietnam might not work in another due to regional and/or population density differences—which means that solutions need to be truly localized by community stakeholders. How can new products, services, and solutions be developed at local levels—while at the same time incorporating existing global solutions into the local Vietnam context?

Further questions:

• How can exponential technologies accelerate Vietnam’s developmental story?

• What should local entrepreneurs focus on considering existing resources and technologies in Vietnam?

• What kind of experts does Vietnam need?

• Can Vietnam’s societal challenges be overcome?

• What areas or industries will need constant attention to achieve “Vietnam 2035”?

Chapter 11: Being a Part of Vietnam’s Success

This chapter will include advice for policy makers and foreigners who want to play a part in Vietnam’s future development. How can you be a part of Vietnam’s success?

Further questions:

• How can foreign entrepreneurs and investors get more involved in Vietnam’s development story in smart ways?

• What’s the best way to get started?

• What are the resources for entrepreneurs in Vietnam?

• What are the best kinds of programs for interested investors to create in Vietnam?

• What are some lessons learned?

Proposed/completed interviews/quotes (non-exhaustive):

• Phan Quang; Deputy Director, Asian Development Bank (Hanoian)

• Jon Baer; author of Decoding Silicon Valley: The Insider's Guide and partner at Threshold Ventures

• Vu Duc Dam; Deputy Prime Minister of Vietnam; supporter of startups

• Brian Cotter; lead of the UNICEF Innovation Lab in Vietnam

• Christopher Zobrist; Center for Mindful Learning

• Tran Tri Dung; the Entrepreneurial Programme funded by the State Secretariat for Economic Affairs (SECO) of Switzerland

• Dr. Ev Myers; former Fulbright Professor, Vietnam National University and former Fulbright Specialist, Thai Nguyen University

• Bernard Seys; cofounder of Efaisto

• Vanessa Santamaria; cofounder of Memeapp

• Barbara Ximenez; cofounder of Shutta

• Thu-Ha Pham; APAC regional manager, AngelHack

• Jeffrey Paine; managing partner of Golden Gate Ventures

• Ryu Hirota; principal of IMJ Investment Partners

• Shuyin Tang; principal of Unitus Impact

• Douglas Abrams; CEO of Expara Ventures

• Binh Tran; venture partner, 500 Startups Vietnam

• Pham Hong Quat; Director of National Agency for Technology Entrepreneurship and Commercialization, Ministry of Science and Technology

• Aaron Everhart; cofounder of HATCH!

• Hoi Nguyen Ba; founder of Fablab Da Nang

• Ha Dau Thuy; cofounder and chair of the BOD of OCD Management Consulting

• Marion Vigot; founder, Ma Belle Box

• Hieu Tran; former Ministry of Industry and Trade official/ ASEAN Secretariat official

• Justin Nguyen, operating advisor for Vietnam, Monk's Hill Ventures

Background

• There are over 1,500 startups operating in Vietnam, with an increasing number of foreigners going to Vietnam with the intention of establishing startups. 500 Startups, a venture fund based in Silicon Valley (with operations in Vietnam), plans to fund 100 startups in Vietnam over the next three years with a $10 million fund. This target amounts to one startup per week but there are currently only 200-300 applications for any incubator/accelerator in Vietnam. Thus, the number of active entrepreneurs pursuing startups has to significantly increase in Vietnam—whether local or foreigner—for 500 Startups Vietnam to meet its target.

• According to the cofounder of Startup Weekend, Vietnam’s population alone has the capacity to boost the number of team applications per program by 2,000-3,000.

• Launch, the members-only global Facebook group for Vietnam’s startups now has more than 30,000 members, up from 20,000 one year ago with daily questions and comments posted in Vietnamese and English. However, the sections on Vietnam Startups in Quora have not been updated in two or three years, so primary information about Vietnam’s enterprise ecosystem is maintained by gatekeepers.

Primary Market

• Current and additional Singaporean founders/entrepreneurs looking to source quality developers (“ready to deploy” teams) in Vietnam;

• Current and additional regional investors from Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand, and Japan who are interested in the burgeoning Vietnamese market;

• Current and additional international entrepreneurs from Europe (UK, France, Switzerland, Finland, and Germany) who are looking to develop their prototype for less money than it would cost in their home markets;

• Current and additional investors (venture capital, private equity, and impact) from the U.S. (primarily Silicon Valley and New York City) who are increasingly looking to frontier markets;

• Current and additional intentional and “accidental” entrepreneurs from the U.S. (~400,000 Americans visit Vietnam annually);

• Vietnamese-Americans (2+ million in the U.S.—half live in California and ~100,000 live in San Jose, the heart of Silicon Valley; almost 200,000 live in Orange County, California, close to Hollywood; and ~35,000 live in Houston, Texas, a production center for the Oil and Gas industry);

• Members of the Vietnamese diaspora in English-language markets such as Canada (~150,000) and Australia (~180,000); and

• American students who study in Vietnam, thereby demonstrating their interest in the country (1,000 during the 2013-2014 academic year).

Secondary Market

• High school students curious to learn about Vietnam outside the lens of “containment of communism” as taught in Advanced Placement American History (~400,000 sat for this exam in 2011);

• The almost seven million Vietnam War-era veterans who are still alive and might be curious about the changing legacy of Vietnam;

• Incoming diplomats (on two-to-four year tours) to Vietnam who have a commercial or economic focus and need to “ramp up” quickly—over 80 Missions in Hanoi and 25 Missions in Ho Chi Minh City;

• Digital nomads or location-independent freelancers who want to dive a bit deeper into their Vietnam experience;

• Professionals at The World Bank, International Monetary Fund, UN agencies, or NGOs; and

• Business and political science professors; and college students who focus on globalization, developing economies, and/or Southeast Asia (see below).

Kieu-Linh Valverde, Associate Professor in the Asian American Studies Department at UC, Davis, and author of Transnationalizing Viet Nam sent the following email:

“I really look forward to reading [Startup Vietnam] if I'm able to have an early copy for review. I actually would love to teach it in my class Winter 2017 on development if possible. The main class project will be group start ups!”

Members of the Vietnam Global Insight Expedition (GIX) at Tuck Business School, Dartmouth College (25 students) traveled to Vietnam last year in their efforts to:

“…study Vietnam’s business environment given several post-war decades of rapid social and economic change, evolving capital and investment flows, political balancing of communist ideology with capitalist growth, and the country’s increased integration in international trade and labor regimes.”

Similarly, seven MBA students from the Kelley School of Business, Indiana University visited Ho Chi Minh City last year to:

“…[work] on a project with a Vietnamese start-up company for the past three months now. Currently, we are in Vietnam and working to align the company's future goals with potential investors.

The client is a three year old company which is doing extremely well, but has been unable to reach its maximum impact/ potential. The client is looking for a strategic investment which can assist the company both financially as well as technologically.

We were in [Ho Chi Minh] city this whole past week working with the client on-site.”

University of California, Davis; Dartmouth College; and Indiana University current and future students (with similar profiles and interests) all would be interested in reading Startup Vietnam.

I regularly share content on Twitter and LinkedIn (combined 2,023 followers as of September 13, 2017) related to Vietnam. I have established a dedicated site for the book, www.startupvietnambook.com, which will include all of the published content I have created on Vietnam relating to startups, innovation, and technology.

Three major sites focus on my topic in the region—Tech In Asia, e27, and Tech Wire Asia—and I have contributed to all three. I have guest blogged every month (rotating) since February 2015 to reach visitors via sites such as Tech In Asia (2.5+ million unique monthly visitors), e27 (250,000 unique monthly visitors), and Tech Wire Asia (190,000 unique monthly visitors). I have received invitations to return on each site, plus I’ve made contact with several other U.S.-based publications for potential future guest posts. Between 2015 and 2016 my articles on Vietnam’s tech scene were shared over 1,500 times and generated almost 8,000 likes on various social media. An article (August, 2016) on a third-party platform received almost 1,000 hits per day during a two-week period. Another article (January, 2017) received 5876 hits with average time of 1:45 spent on page. I will continue to contribute content on these platforms and I am currently targeting Quartz, MIT Technology Review, and Harvard Business Review.

In 2015, I was asked to moderate a panel on Big Data and Social Media at the first-ever Techfest Vietnam conference in Hanoi, which was attended by ~1,000 people with support from Vietnam’s Ministry of Science and Technology. Additionally, I was moderator for two sessions at last year’s TechFest Vietnam.

As part of market research and promotional efforts, I will start giving presentations on the economic developments and entrepreneurial opportunities in “Startup Vietnam" to relevant and interested audiences in the United States. In May 2017, I traveled to University of California, Davis for a Viet Nam Cluster Meeting hosted by Professor Kieu-Linh Valverde, who is spearheading the New Viet Nam Studies Initiative—which denotes contemporary or 21st century Vietnam. This event was a good opportunity to get feedback on the current manuscript, which is over 130,000 words; the final product will be approximately 65,000 words. In June 2017, I gave a talk on Vietnam and startups at New York University: http://bit.ly/NYUFLVN

Professor Balbir Bhasin, Ross Pendergraft Endowed Professor of International Business at the University of Arkansas, Fort Smith has invited me to address his classes on my professional experiences in Vietnam.

In November, 2017, the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) Summit will be held in Da Nang, Vietnam. Over 20 Member Economies will be represented across over 400 events, mostly in the Fall. The Summit will be attended by various leaders, including the President of the United States. I plan to distribute promotional materials for Startup Vietnam to various delegation members in attendance at select events in addition to talking/moderating at certain side events in the run up to, and during APEC Leaders Week.

The book, Startup Asia: Top Strategies for Cashing in on Asia’s Innovation Boom is five years old. Another book, Vietnam 2014: New Information and Cultural Insights Entrepreneurs Need to Start a Business in Vietnam, is three years old and has not been updated with critical changes to 2015’s national legislation.

Deal Street Asia, a website with offices in Singapore, also covers startups, but focuses more on funding, investment, and financial markets.

Vietcetera is a cultural blog featuring personal interest stories including entrepreneurship. Anh-Minh Do, a Vietnamese-American, is cofounder. He was the Vietnam editor for Tech In Asia (living in Ho Chi Minh City), but now works at Vertex Venture in Singapore, where he lives. He contributes to Forbes.

Tech In Asia and e27—the most well-known regional portals—do not have dedicated tech reporters covering Vietnam; they rely on correspondents based in The Philippines, Indonesia, or India to report on Vietnam. Tech In Asia and e27 do utilize contributors, but the quality is uneven and/or commentary is provided by individuals who have limited experience in and/or exposure to Vietnam.

Bobby Liu occasionally contributes to e27; he now works as a senior director and evangelist for Topica Edtech Group, an Edtech startup expanding into Southeast Asia. He also focuses on Bangkok, as he is co-director of the Topica Founder Institute Bangkok, an incubator for startups in Thailand.

Jon Myers, a location-independent entrepreneur, has written about the benefits of living in Vietnam for Virgin. He is a design consultant for corporations; comments on his articles indicate that readers would like to know more about operating in Vietnam.

Brett Davis writes about modern Vietnam (as a contributor for Forbes), but takes a much broader approach in that he doesn’t focus solely on startups, innovation, and entrepreneurship.

Bloomberg, Reuters, Forbes, CNET, The Wall Street Journal, The Economist, and BBC News all have published articles about Vietnam’s growing startup potential in the last year or two. However, these articles lack context or the bigger picture of the shaping trends over two or three years as they are just snapshots. (These reporters usually "parachute in" for a week or two.)

Saigoneer is a Saigon-based blog that does some reporting/featuring on some startup topics but it is not a core focus for the publication.

The Word, a Vietnam-based magazine and online portal, features a “Startup of the Month” section.

Director of GKTA Group and regularly writes about startups, innovative technologies, and entrepreneurship in Southeast Asia.

250 copies • Partial manuscript.

Anaphora Literary Press was started in 2009 and publishes fiction, short stories, creative and non-fiction books. Anaphora has exhibited its titles at SIBA, ALA, SAMLA, and many other international conventions. Services include book trailers, press releases, merchandise design, book review (free in pdf/epub) submissions, proofreading, formatting, design, LCCN/ISBN assignment, international distribution, art creation, ebook (Kindle, EBSCO, ProQuest)/ softcover/ hardcover editions, and dozens of other components included in the basic package.

500 copies • Complete manuscript.

Blooming Twig is an award-winning boutique publishing house, media company, and thought leadership marketing agency. Based in New York City and Tulsa, we have represented and re-branded hundreds of thought leaders, published more than 400 titles in all genres, and built up a like-minded following for authors, speakers, trainers, and organizations with our bleeding-edge marketing strategies. Blooming Twig is about giving the people with something to say (“thought leaders”) a platform, walking its clients up to their own influencer pulpit, and making sure there is a like-minded crowd assembled to hear the meaningful message.

500 copies • Completed manuscript.

HigherLife allows authors to retain all your publishing rights and you pay no publishing fee. Your only cost is to purchase at least 2,500 copies of your book from the initial press run, and this cost typically amounts to a 60%-80% discount off retail. You benefit from a full publishing team of experts: editors, designers, publishing and marketing strategists, copyeditors, copywriters, who know how to take your message and craft it as well as any New York Times best-selling publishing house would do.

Looking for entrepreneurship, business, self-help, and personal growth books.

Morgan James Publishing has revolutionized book publishing—from the author’s standpoint, earning 29 NY Times and over 100 USA Today and Wall Street Journal best sellers. We teach authors strategies to leverage their books and grow their businesses—adding value while staying out of the way. Evidenced by more Major Media best sellers than most publishers our size. Regularly ranked by Publishers Weekly as the most recognized and one of the fastest-growing publishers in the nation, Morgan James is reported to be “the future of publishing.”

250 copies • Completed manuscript.

Motivational Press is a top publisher today in providing marketing and promotion support to our authors. Our authors get favorable rates for purchasing their own books and higher than standard royalties. Our team is at the forefront of technology and offers the most comprehensive publishing platform of any non-fiction publishing house including print, electronic, and audiobook distribution worldwide. We look forward to serving you.

Next Century Publishing is a world leader in book publishing, book marketing, and providing authors with the best platforms for success. NCP is a cutting-edge publisher that refuses to accept the status quo. Our mission statement is to change the way people write, read and experience books!

The game has changed, and today’s authors have more choices than ever. NCP utilizes the latest in social media and technology to increase readership, book sales, and bottom-line profits for its authors. The company is truly unique in that both independent publishing and full-royalty publishing are offered under one label. NCP is already being recognized for its innovations in marketing, social media, and media awareness.

As a wholly owned subsidiary of http://ReadersLegacy.com, our authors benefit from added training and exposure on the publishing industries fastest growing community of avid readers, authors and publishers.

Next Century Publishing is also launching several web-based campaigns aimed at disrupting and reinventing the mammoth publishing world, while bringing greater value to our authors.

250 copies • Partial manuscript.

Authors Unite helps you become a profitable author and make an impact. We take care of printing and distribution through major online retailers, developmental editing, and proofreading with unlimited revisions. We take care of the entire process for you from book cover design all the way to set up your backend so all your book royalties go straight to your bank account. We can also help with ghostwriting if you prefer not to have to figure out all the steps on how to write a book yourself.

With our book marketing services, you don’t need to worry about figuring out all the steps on how to market a book or how to become a bestselling author. We’ve helped hundreds of authors become bestselling authors on Amazon, USA Today, and The Wall Street Journal. We take care of the entire book launch process for you to help you sell thousands of copies of your book and become a bestselling author.

View case studies here: https://authorsunite.com

100 copies • Partial manuscript.

Bookmobile provides book printing, graphic design, and other resources to support book publishers in an ever-changing environment. Superior quality, excellent customer service, flexibility, and timely turnarounds have attracted nearly 1,000 satisfied clients to Bookmobile, including trade houses, university presses, independent publishers, museums, galleries, artists, and more. In addition, we manage eBook conversions and produce galleys, and regularly provide short-run reprints of 750 copies or fewer for major publishers such as Graywolf Press.

100 copies • Completed manuscript.

Happy Self Publishing has helped 500+ authors to get their books self-published, hit the #1 position in the Amazon bestseller charts, and also establish their author website & brand to grow their business. And the best thing is, we do all this without taking away your rights and royalties. Let's schedule a call to discuss the next steps in your book project: www.meetme.so/jyotsnaramachandran

Get your ebooks into the biggest stores and keep the 100% of your royalties. Amazon, Apple iBooks, Google Play, Kobo, Nook by Barnes & Noble and more.

At Xlibris, we provide authors with a supported self-publishing solution from our comprehensive range of publishing packages and associated services. Publish and distribute your book to a global audience in classic black & white, dazzling full-color, paperback, hardback, or custom leather bound formats, plus all digital formats.

Chapter 3: Vietnam Up Close

Coming as You Are

One of the first things that you might notice in Vietnam is a completely-covered person—usually a woman—zipping along on a motorbike, like a Pac Man ghost. There is this obsession over staying out of the sunlight for fear of darkening one’s pale skin. Then, after some time in Vietnam, you might realize that the Vietnamese men have a pretty sweet deal when it comes to household responsibilities: they usually consist of drinking and smoking with their buddies due to the patriarch society structure.

So with these two concepts in mind, it should come as no surprise that the experience of a white male in Asia may be unrivaled in its totality. Everything from preferred treatment to exclusive access is available for the taking. Constant discrimination (against the local populous) can be real and ugly, akin to a second-class, tiered system where—in a professional environment—the locals may sabotage each other in order to curry favor with foreigners in one instance, and then band together to shift blame onto foreigners in the following moment. Some locals might even seek to “collect” foreign friends for the prestige and status it brings.

This preferential treatment sometimes makes it difficult to forge connections with young Vietnamese who are often intimidated when speaking English with foreigners. And it’s hard to know exactly what the motivations might be of individuals who “latch” onto foreigners. It’s also dangerous to operate in Vietnam with a superficial knowledge of the culture—for, in doing so they run the risk of being a “white face” to promote various projects. At the worst and most basic level, foreigners are looked at as “walking ATMs,” and are treated as such when buying simple items like bananas—but these experiences are for tourists most of all.

However, Americans should feel reassured that this discrimination is not based on their passport. (Quite the opposite: according to a 2014 Pew Research Center survey1, 76% of Vietnamese “expressed a favorable opinion” of the United States—in 2017 84% of Vietnamese respondents2 said they now have a ‘very or somewhat favorable view’.) But for some, this dual spirit of infatuation with race (white) and sex (male) can go to their head. Indeed, being treated like a king can become addictive. Sadly, it can get out of hand as arrogant and hedonistic tendencies may develop, especially in a place like Saigon where the limits of excess during a night out on the town seem hard to identify and even harder to reach. (In recent years, posh rooftop bars in Saigon have sprung up almost as fast as co-working spaces have.)

The risk of overstimulation is real, especially with several strongly caffeinated Vietnamese iced coffees during the day, and copious drinks with a mix of (real or fake) alcohol late into the night. Visiting Vietnam for the first time is almost a primal release where anything is possible—shocking in a way and exhilarating in another. But that’s Asia: the illusion of freedom in the streets because your input doesn’t matter at the state level.

“Freedom” includes public drinking, public intoxication, and general lawlessness... if you can get away with it. Drunk driving is punished by a fine, paid on the spot, or by injury (including death), whichever comes first. Foreigners can sometimes succumb to these dangerous local mentalities as they explain away otherwise reckless behavior. In a less extreme example, existing biases may cloud one’s ability to appreciate progress—of developing relationships, standards, and quality—within the local context. Vietnamese-American Christopher Zobrist, a pioneer in innovation and entrepreneurship in Vietnam, expands on these kinds of challenges:

“Coming from a developed country that churns out high quality products as well as infrastructure (roads, public buildings, etc), Americans as well as people from other developed countries have a natural expectation to see and make things at a high standard of quality. Vietnam is still a developing country, so many things are made with what little resources were available, and so the expectation for quality coming from domestically produced goods is not high.”

So foreigners and locals might have completely different ideas on a given subject or context, which might be further compounded by limited communication skills between both sides. A foreigner might keep hearing, “yes”, but nothing may happen as a result of the conversation. As a guest in Vietnam, it can be difficult to square what one sees with what one hears—and in fact, neither may be completely accurate. Asking the same thing in different ways might reveal some additional light on the situation, but often, the generally accepted approach might only suit Vietnamese startups within the country’s borders, especially for those who wish to expand regionally or internationally.

Stefan Van Der Bijl, managing director of Cofounder Venture Partners, a venture builder in Ho Chi Minh City, shares his initial impressions of Vietnamese startups and whether or not they can go global:

“I think they can, but have not found their mojo yet. Most of the startups I see are blatant copies of others outside [Vietnam]. If they copy[, then] they lose first-mover advantage, are a me-too play. Few have original ideas. Translating something that worked abroad does not mean will work in [Vietnam] or vice versa. [Vietnam] has 90 [million] people, they should only need develop internally, see from there about expanding abroad. The timezone difference is a real problem for anything involving direct communications--best would be for them to have offices outside [Vietnam]--few can afford ([would] be nice to have [Vietnam] government-sponsored office space abroad for [Vietnam] startups). Only some [Vietnam] startups really have an idea what it's like to work at startups that have clients round the clock--they tend to be comfortable. Haven't had [international] exposure, their experience is only [Vietnam]. [Vietnam] startups can get 90% of the way, the remaining 10% fit and finish is where they fail.”

Even regional foreigners might have some trouble acclimating to the way things are done in Vietnam. Koreans and Japanese definitely have advantages based on similar business and cultural rituals, but it can even take some time for Asians to get used to the challenges. In a 2017 BBC article, couple Yosuke and Sanae Masuko, cofounders of Pizza 4Ps, a wildly popular establishment that is expanding rapidly, shared their story of how the institution came to be in 2011—and some challenges along the way. On working styles between Vietnam and Japan, Ms. Masuko said, "We found the gap of working culture between Vietnamese and Japanese is the one that is difficult to bridge... but things are improving."

While there are advantages to having been in Vietnam long-term, being a fresh-faced foreigner can be an asset as well—especially in identifying opportunities. John Wise and Wombi Rose, cofounders of LovePop, were inspired by something they saw while traveling in Vietnam. According to the duo:

“…we found ourselves on a school project in Vietnam, [and] we fell in love with the unique art form of beautiful, hand-crafted, paper cards. Our inner engineers came to life with the world of possibilities – we wanted to create everything as a delicate paper sculpture!”

At the time, the LovePop founders were students at Harvard Business School and launched the company from the Harvard Innovation Lab in 2014. The team went on to join Techstars in 2015 and was featured in Shark Tank, raising over $9 million in six rounds along the way. All because of a trip to Vietnam.

But not everyone who comes to Vietnam is ready or able to add value to the projects in-country. Being a foreigner in Vietnam is an opportunity to reinvent oneself—but not everyone appreciates this reality. Thus, culture shock may cut in two ways: one as being a minority in Vietnam, especially if you are not used to being one; and two, making sense of expat society, especially whom to trust as you grow tired of meeting people only to have them disappear months—or weeks—later.

Then you might start to notice more contradictions in Vietnam. At times, the experiences in Vietnam can be absolutely crazy. Things are slow until they are not. Vietnamese rush through traffic on their motorbikes as if their lives depended on getting to their destination as soon as possible—only to do nothing but sit and sip coffee or tea once they arrive. But for yours truly, Vietnam is a gem in Southeast Asia. However, it’s not without its own set of challenges.

Thus, Vietnam is a place where, if you "stick it out" for a year or two, you may be able to make a blend of both the foreign and local benefits. But there are many challenges along the way, and people will come and go. Having real local friends helps—not just people to drink with and who want to practice English with you. Only then will you see deeper aspects of Vietnam up close.

Expectations, Social Context, and Miscommunication

Coming to Vietnam and doing things the way they are done back home is a recipe for a long and hard haul to produce sub-optimal results. In other words, it will be a disaster. First, there are many pitfalls in Vietnam. It’s an easy place to have hours turn into days, and eventually weeks without anything tangible to show for it. Bad habits can develop quickly and are often hard to break. Ask for perfectly acceptable things as you would in any other country (such as a dry napkin) and the likely response in Vietnam is a variation of, “Your requirements are too high.” If you are unlucky enough (Vietnamese are highly superstitious) to get scammed—and you will, one way or another, so get ready for it—the person on the other side will be smiling the entire time and even long after the transaction has concluded.

Within this context, it’s easy to remain within the expat community and bypass any misunderstandings. But for those who have long-term plans for or in Vietnam, it’s a wasted opportunity to live in a country without actually experiencing it. On the other hand, some expats (and Viet-Kieu—the Vietnamese who were born in another country besides Vietnam) go too deeply into Vietnam, i.e., they have been in-country for so long that they begin to adopt local practices—and not the best ones. After all, Vietnam is not a best-practices paradise (except for its vices such as smoking and drinking), although some can fool themselves into believing the opposite is true.

If you are still interested in Vietnam, then read on: everything in Vietnam is built on relationships—with whom and how strong. And from an enforcement perspective, contracts—which Westerners often love to reference—are essentially worthless. And if “push comes to shove,” litigation is handled behind-the-scenes, as the outcome largely depends on which party has deeper pockets. In reality, contracts serve as acknowledgements that there is an existing relationship between two people or organizations—but it’s up to both parties to keep that relationship in good standing. As one might imagine, proximity to and goodwill with government officials is a competitive advantage—but not one without some risk depending on the exact nature of the relationship. For some foreigners or Viet-Kieu, that means marrying into a powerful family in order to cut through the reams of red tape that blanket every aspect of Vietnamese society.

Some expats do indeed choose to marry into Vietnam and route everything through their local spouse. This option works if there is a solid foundation and mutual understanding, as in any genuine relationship. But the less time an expat has spent in-country, the higher the chances for cultural misunderstandings. For one, relationships and responsibilities take on different meanings between the urban and rural parts of the Vietnam. Furthermore, the roles of men and women are quite different compared to the modern and Western interpretation of equality, romance, and social obligations. Scroll through any Vietnamese expat-oriented Facebook group and you will find that it is full of these misunderstandings, which (of course) can only be resolved in the court of public opinion.

The majority of relationships between locals and foreigners (for business) begin over coffee, and usually progress toward the end of the night near the bottom of a bottle of alcohol (though not always in the same sitting). Facebook (once banned in Vietnam) is the preferred social network to connect with others for business opportunities—not LinkedIn. So more often than not, the line between personal and professional relationships is so blurred that life becomes a series of interactions to help one another in every aspect of livelihood.

Yet, having a trusted local by one’s side can be the difference between success and failure as Vietnam has a steep learning curve; who and what is right is not always clear in the local context. This is true in many Asian and Confucian cultures, so it can take some getting used to coming from the West. Dr. Everett Myers, a former Fulbright professor at Vietnam National University, has been living in Vietnam since January 2015. Previously, Dr. Myers was a professor at New York University, with extensive experience in Japan. He suggests:

“Significant ambiguity [exists] in the rules and regulations and most importantly in their implementation and enforcement. Foreign[ers] should expect a heightened degree of scrutiny in any of their business dealings. As such, a local partner to help navigate the local territory is a must for many foreign enterprises in Vietnam.”

Triangulating what and who is the "real deal" can take up a great deal of time, and even expand into more than one city. Expats may experience scams from their leasing agent all the way to fellow expats. But figuring out why things are the way they are, i.e., understanding the explicit and implicit set of cultural rules that dictate what happens in daily life helps to minimize risk. Dr. Myers offers:

“The principal pitfall to avoid is falling into the ‘value trap’, i.e., making value judgments on Vietnamese society as contrasted with the West. Once one enters this trap they will find themselves in a 10-foot hole with a five-foot ladder... tough to get out of. Avoid the value judgements and simply recognize the differences... this will help reduce the anxiety and enable one to better navigate the Vietnamese landscape.”

Newly-arrived foreigners sometimes complain about locals not being straightforward or even lying. Locals might consider this “bending the truth,” as (to them) white lies are more-often-than-not perfectly acceptable. One of the biggest contributions to failure is not setting the right expectations on both sides. There’s an often repeated saying in Vietnam that holds: “The longer you stay in Vietnam, the higher your patience, and the lower your effectiveness.” While that may be true for some segments of expats (or immigrants), many foreigners in Vietnam would disagree. But for all the successful or prominent expats in Vietnam, there are others who were chased, kicked, or effectively driven out of the country.

Thus, there are many skeletons in closets across Vietnam. At times, it truly feels like the “Wild East.” Ultimately, it’s difficult to get accurate information about what is going on without asking a bunch of people close to a source and arriving at your own opinion. Standards vary, as does consistency of many things. The resource that is in the shortest supply is talent (this is true across Southeast Asia) as there are many examples of local organizations valuing perceived loyalty over competence.

And if loyalty is not a factor, then age dictates in every social situation. (The power distance between men and women in Vietnamese culture already is great.) So if—like your author (at one time), you are a 26 year-old foreign consultant working with a 50 year-old local manager—you will be wrong if you don’t agree with the “facts.” Imagine Vietnamese students working with local investors—who presumably have money and are significantly older. It creates an imbalance in the force and flow of capital, which may be even more pronounced if the sexes are opposite.

Overall, Vietnam is not a place to learn best practices (except how to navigate in a developing economy, i.e., risk management): companies regularly use unlicensed software, employees display extreme examples of unprofessionalism (such as viewing pornography during lunch time), and most organizations are run from a top-down approach in a micro-managed style.

However, Vietnam is great if you are trying to do something new. Meaning, if you take a look at the West, everything is developed: industries, infrastructure, institutions. In places like Vietnam, you can create and shape new markets. Yes, it is labor-, time-, and capital-intensive—but it is also a place where demographic and economic projections promise the creation of massive amounts of value well into this century.

Yet, this is a long-term approach—something that may clash with local counterparts. A perceived weakness in Vietnam is the short-term orientation that many people seem to take. “Quick fixes” and the like are preferred over fundamental solutions to provide lasting improvements. Part of this attitude emerges from the educational system which is based on Confucianism. “Saving face” is always touted as an Asian characteristic, which sounds nice and sensible until you see it in practice. Ask someone for directions and instead of saying “I don’t know," you will be pointed in the wrong direction. Ask if a particular task has been accomplished, and you’ll be met with a resounding “Yes, yes!” —only to find out it hasn’t even been started yet.

Perhaps that is why it’s not uncommon to encounter foreigners who have been in-country for less than six months to have an obvious analysis for everything that is wrong with Vietnam, which usually includes some aspect of the North. Even within Vietnam (in places like Ho Chi Minh City) Saigonese and expats alike will warn about the dangers of traveling to Hanoi. As the refrains go: "The weather sucks;" "Don’t do business with the Hanoians, they will cheat you;" "They aren’t friendly;" and "The traffic is worse than in Ho Chi Minh City." Some of this is true; the weather is indeed better in Saigon.

But pry a bit deeper and you might be surprised to learn that the same locals who are giving you advice have only “visited Hanoi once a few years ago.” And many of the same foreigners dishing out tips to avoid the city have never visited Hanoi since their local friends “advised against it.”

Hanoi, Ho Chi Minh City, and Da Nang are all distinctly different in culture, language, ways of thinking, and simply doing things. These major distinctions are lost for those who only spend time in one area of Vietnam. Of course, it’s much easier for a northerner to do business in the south and also easier for a foreigner to operate in Hanoi than it is for a southerner (due to stereotypes and biases based on regional accents). But the key to better understanding Vietnam is knowing that your business model developed in Ho Chi Minh City probably won’t work in Hanoi, and might not work in Da Nang due to cultural and regional differences. (And for those with a larger vision, the deeper you go into Vietnam, the harder it is to go regional.)

A Tale of Three Cities

Without a doubt, the top three cities in Vietnam are Hanoi, Ho Chi Minh City, and Da Nang. They are all incredibly different—from accents to governing styles and weather patterns—and have varied strengths and weaknesses. Ho Chi Minh City feels like it aspires to acquire the commercial and cosmopolitan aspects of Bangkok or Singapore. There are more publicly visible expressions of art and creativity in the streets compared to Hanoi. On the other hand, Hanoi has a vibrant underground music and art scene, which is sometimes merged between the local and foreigner communities. Of the three major city's public sectors—the Ho Chi Minh City government tries to be progressive, the Da Nang city government is the most accessible, and Hanoi's city government may be the most conservative. (For those who like sleeping in, Hanoi is probably not the city for you as the war-time speakers, which the city considered removing, are still in effect, blasting propaganda twice a day starting around 7:30 AM.)

It’s not uncommon for young Hanoians to move to Ho Chi Minh City to escape the pressures and expectations from their families in the North. In general, women are expected to live with their families until marriage, usually before the age of 25. At that point, they move in with their husband (and sometimes his family) and prepare to raise children. In Hanoi, first comes the baby and then the marriage, to ensure that the grandparents will be pleased. However, in recent years, women are waiting longer to be married—until 30 or even later. But they also run the risk of being labeled ế or “spoiled” by their communities. If a young woman does move out from her home before marriage, then it’s probably to live in another city as from a rural area to an urban center—although there are some exceptions to this “rule.” So those who never leave Ho Chi Minh City (especially foreigners) may fall into the trap of believing that Ho Chi Minh City is Vietnam and vice versa. But it’s not: almost 70% of Vietnamese live in rural areas.

During a 2015 meeting at the American Center at the U.S. Consulate in Ho Chi Minh City, about 60 entrepreneurs, investors, and other community builders gathered to discuss the major challenges confronting the ecosystem. Led by a local and a Vietnamese-American, the session attempted to identify the needs of the community. There were three or four participants from Hanoi, most of whom were foreigners. As the conversation swirled around the room, it became clear that (for the majority of the participants) the “startup ecosystem” ended at Ho Chi Minh City’s limits.

One of the complaints concerned the inability to access the right networks as well as lack of cooperation among members of the community—quite a different experience from working in Hanoi. Thus, some needs are local, and some needs nationwide. Cooperation among the players—or lack thereof—can make a major difference in developing things on the ground. But it still has a long ways to go.

As one Vietnamese-Australian put it, “There are 10 different communities in Ho Chi Minh City trying to do the exact same thing.” Perhaps this is an exaggeration, but the atmosphere in general is different in Hanoi. To provide just one example, there are fewer Viet-Kieu in Hanoi, especially American Viet-Kieu. The diplomatic community is more obvious and accessible in Hanoi as well. The expats who are there genuinely like Hanoi, or are building government relationships.

Contrast that to Ho Chi Minh City, which accounts for approximately 25% of Vietnam’s GDP, and where the focus is on all things commercial, nightlife, and glamour. Ho Chi Minh City’s nightlife can certainly be dangerous for your liver and your wallet. It’s a place where you can stay out until sunrise one night—and do it all over again the following night. On the other hand, Hanoi has a general closing time at midnight for drinking establishments—but for those in the know, the party moves to speakeasies. (And Hanoians like to start drinking earlier, too.)

Saigon (the name still used to refer to Ho Chi Minh City within its city limits) is a city that lives by partying. Compare the local bia hoi in Saigon, which are wide open, colorfully-decorated, and full of drinking chants and mirth—with those up in Hanoi (for locals), which are sparsely decorated and narrow and you will definitely feel a difference. (Of course, you are not expected to tip in Hanoi like you are in Saigon.)

Da Nang is almost exactly in the middle (in both geography and neutral setting) between Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City. It has qualities that neither Hanoi nor Ho Chi Minh City can match. It’s a coastal town with fresh air and opportunities for biking, surfing, and hiking. In the 1990s, the city openly modeled itself after Singapore in its developmental aspirations so Da Nang has a great deal of potential to develop as a foreign startup hub. Da Nang also perfectly embodies and reflects this city’s position at the center of globalization changes and has the potential to lead the way in the future. But cheap labor is not a sustainable competitive advantage, and Vietnam will have to move up the value chain if it seeks long-term to be competitive with other developing countries.

So what is the context for operating in Vietnam as a foreign entrepreneur? Well, foreigners can never compete with Vietnamese on a labor rate basis—the minimum wage (in 2016) is somewhere between $107 and $156 per month, depending on urban or rural areas. In addition, “commissions” (as considered in the west) aren’t really commissions. Within organizations, different managers (Finance Manager, Technical Manager, etc.) vie for contracts, sometimes depending on the largest commission. These contracts are then fulfilled via a director’s network from their staff all the way to the delivery drivers to pick up the equipment. Local partners usually handle these “marketing fees” for foreign companies.

In such an environment, it can be quite difficult for an American to do business where s/he is a guest, without the same networks or experience of “traditional” Vietnam, such as “coffee money.” (Younger Vietnamese—although they acknowledge, coffee money and envelopes—are less likely to share the same attitudes.)

So unless you want to do things “local style,” you must find other ways to add or create value. Building relationships in Vietnam takes time: lots of (hours-long) coffee meetings can be compressed into several beer drinking sessions. These (usually inebriating) sessions can be compressed into a karaoke lounge stop. Overall, people generally are quite accessible in Vietnam, and generally are willing to extend their networks and knowledge. (Though it’s easier to get "burned" in Hanoi if a prominent member of the community doesn’t vouch for you.)

However, there are no shortcuts to building trust—unless via a trustworthy introduction. Credibility, authenticity, and reputation are everything.

Things are a bit more open-minded in Ho Chi Minh City City, but it just means that it takes longer to build rapport to a deeper level. The most likely places to build social cohesion are bars, restaurants, lounges, or clubs. Thus, it can sometimes be hard to tell if an engagement is a business meeting, a get-together among friends, or a mix.

In Hanoi, Hanoians are a bit better at separating business and pleasure, but often not by much. (However, they can be known for becoming “unleashed” in Saigon during a weekend getaway.) For Westerners (and especially newcomers), coming to Vietnam is like being plopped down in a place where there are no rules for conduct. No one will tell you to go home (except at midnight in Hanoi—although this rule is relaxing), and no one will refuse to sell to you. You are free to do whatever you want—and that’s intoxicating in its own dangerous way. It’s almost the opposite of a "nanny state" (with the exception of acceptable content) and it definitely is a capitalistic "survival of the fittest" approach to see who can outlast whom.

Many local behaviors (which foreigners would classify as rude) are the result of this survival mode. Vietnam is still in transition to a society of self-expression. Facebook has been one outlet but, more often than not, opinions seem to be of extremes. Civics and civility have yet to be mastered in the online as well as physical domains—which can be frustrating when dealing with nuanced subjects. As we’ll see in the next chapter, there’s more than meets the initial eye to Vietnam.

Howdy!

In the last update I shared that my podcast would be launching soon and that day is today! As I mentioned, I recorded 19 …

Startup Vietnam launched on April 2, so it's been a bit over three months since the launch date! Since then, I spent five weeks in …

Hi Everybody,

Startup Vietnam: Innovation and Entrepreneurship in the Socialist Republic officially launches today, April 2! (Video message below.) Woohoo!

Furthermore, I am proud to announce that Startup …

Dear Everyone,

Unless you received an email from me, your copy or copies were shipped last week!

For those of you in the US, some have …

Dear All,

If you haven't already, please check for an email from SendOwl for a link to download your copy of Startup Vietnam: Innovation and Entrepreneurship …

Hi All,

Hope your summer is going well! Startup Vietnam has a new publisher, Mascot Books, based in Herndon, Virginia.

This is great news …

Dear Early Backer:

Later this month, on May 16, I will receive the final digital proof from the editing team in Singapore. It's taken a bit longer …

Hi!

I have a wonderful announcement to start off 2018: earlier today, I signed with Firewords, a Singapore-based service publisher to help me bring Startup Vietnam: …

Hi!

I am so glad to have your support for my first book, Startup Vietnam: Innovation and Entrepreneurship in the Socialist Republic.

The campaign …

Very interesting book. Thanks Andrew for your excellent work

Andrew's new book is certain to be the authority on doing business and living in Vietnam. Having read pieces of the manuscript I can affirm that Andrew's writing is equal parts entertaining, interesting and informative for anyone with an interest in modern Vietnam.

Eager to have Andrew's book in on my desk.

Good for you Andrew, excited to read it! Diogo

Congrats! Can't wait to see the results

Congrats! Keep it going!

Congrats buddy! Good Luck!!

A much awaited for book.

Thanks Andrew for your great job!

Purchased! Good luck buddy!

I am glad to start seeing the fruit of your hard work and keen observations about the startup ecosystems in VN

Looking forward to reading it!

Very interested, looking forward to reading this!

Hey Andrew,

Congrats on the release of the book, I'm looking forward to reading it!

Pierre-Antoine (Leflair)

Good luck with the campaign! I hope to find a good reason to start visiting Vietnam regularly again.

done my duty!

Best wishes to you!

All the best for your campaign!

I can't wait to read this!

Thank you Andrew for your great devotion to the development of startup ecosystem in Vietnam!

Thanks for sharing meaningful project :) Good Luck for projects ! Cheers ! P.S I'm currently living in Bangkok, let't catch up with soon :)

Congratulations !

Good luck with the campaign, Andrew! Looking forward to reading the book. - Mai

Best of luck! Branden and Sophia

Andrew and I attended the same college and I am excited to read his professional insights on the dynamics of Vietnam's culture and business environments. BRAVO!

way to go! br, teemu / bizmind

Eager to read it! C´mon everyone, final push! I´m sure Andrew´s book has legs to really far; all it needs is some initial traction.

well done Andrew!

Good luck Andrew! Can't wait to read it!

Looking forward to reading this book. Good luck reaching your target.

Hi Andrew, good luck for the book!!!

Nadina

Hi Andrew, a pleasure to support your publication, and the effort that you have put into it. I look forward to a good read.

Good luck on your way to a best seller.

David

Andrew, congratulations, the book looks really interesting, had to order it. Looking forward to get it soon.

All the best, Juhani

Congrats, buddy! I look forward to reading your book!

Andrew congratulations finally your hard work is paying off we are so proud of you!! My prayers and love are with you. Love mom dad and David

KEEP GOING PAL! STOKED FOR THE NEXT ROUND ON YOUR HOME GROUND! YEW!

Hi Andrew - will tell later delivery address in Finland. When is the due date... baby to come out

Almost there, good luck!

Great initiative!

Cool

Very excited to read your book!

Happy Birthday and best of luck on your publication, man!

-Rich

From Le Hung Viet, JAMJA.vn

Good luck Andrew!

Looking forward to reading your research, very exciting project!

Congrats Andrew!

Done...

Hey Andrew,

Looking forward to reading it.

All the best!

Naz

Good luck

Best of luck bud!

Inspiring work! All best Andrew. - G

Is the book already shipped already ?

$20 Sold out

100 readers

LIMITED

• Early Bird 'Signed' Copy

• Free Ebook (PDF, ePUB, MOBI)

Includes:

$26

28 readers

• 'Signed' Copy

• Free Ebook (PDF, ePUB, MOBI)

• Your name Acknowledged in the book

Includes:

$66

13 readers

• Three 'Signed' Copies

• Free Ebook (PDF, ePUB, MOBI)

• Your name Acknowledged in the book

Includes:

$226

3 readers

• 10 'Signed' Copies

• Free Ebook (PDF, ePUB, MOBI)

• Your name Acknowledged in the book

Includes:

$400 Sold out

1 reader

• 20 Limited Edition Paperback Copies

• Ebook (PDF, ePUB, MOBI)

• Recognized in the first-run print edition, the commercial release edition, and the final Ebook (PDF, ePUB, MOBI)

*Exclusive package for Toong

Includes:

$500

0 readers

• 25 Limited Edition Paperback Copies

• Ebook (PDF, ePUB, MOBI)

• Recognized in the first-run print edition, the commercial release edition, and the final Ebook (PDF, ePUB, MOBI)

• 60-min video consult and exclusive Q&A with Andrew Rowan

Includes:

$500 Sold out

1 reader

• 25 Early Bird 'Signed' Copies

• Free Ebook (PDF, ePUB, MOBI)

*Exclusive package for Swiss Entrepreneurial Programme (Swiss EP)

Includes:

$1900 Sold out

1 reader

• 100 Paperback Copies

• Ebook (PDF, ePUB, MOBI)

• Recognized in the first-run print edition, the commercial release edition, and the final Ebook (PDF, ePUB, MOBI)

*Exclusive package for the Finland-Vietnam Innovation Partnership Programme (IPP)--final shipping price for 100 copies to be determined at a later date.

Includes:

$2200

0 readers

Andrew Rowan to host, or take part in as an expert, a workshop on startups, or entering or doing business in Vietnam.

• 100 Limited Edition Paperback Copies

• Ebook (PDF, ePUB, MOBI)

• Recognized in the first-run print edition, the commercial release edition, and the final Ebook (PDF, ePUB, MOBI)

• 30-min video consult and exclusive Q&A with Andrew Rowan

• Startup Vietnam Workshop:

**This package is valued at more than $4,000

Includes:

$5000

0 readers

• 250 Paperback Copies

• Ebook (PDF, ePUB, MOBI)

• Recognized in the first-run print edition, the commercial release edition, and the final Ebook (PDF, ePUB, MOBI)

• Early access to manuscript with opportunity to give feedback before publication

• 60-min video consult and exclusive Q&A with Andrew Rowan

Includes:

$10000

0 readers

In his Keynote talk, Andrew shares lessons learned from working with startups entering or doing business in Vietnam.

• 500 Paperback Copies

• Ebook (PDF, ePUB, MOBI)

• Recognized in the first-run print edition, the commercial release edition, and the final Ebook (PDF, ePUB, MOBI)

• Keynote speaker

**This package is valued at more than $17,000

Includes:

on Sept. 15, 2017, 7:03 a.m.

I am looking forward to reading it! Congrats on getting this far and all the best for the rest of the journey!